When young men, starting out in life, their eyes wide and dreams uncrushed, say they wish to ‘work in the movies’ (whatever that means), it is because they hope one day to have an office like Charles Finch’s. They don’t make them like this any more — the office or the career. It is a serious room. A study in the proper sense. An accidental curation. There are wooden models of sailing yachts, hand-written letters from royal households, giant monochrome photographs of racing cars and distant relatives, stacks of books as impromptu side-tables, framed magazine covers from past lives.

The office sits at the top of a building behind Piccadilly, with Fortnum’s to the south, Green Park to the west, and Albany to the north. Sunshine pours in through the windows, while the Mayfair soundtrack of construction drills — echoing like machine-gun fire over the ridge — just about permeates the thick old walls. There’s a low leather sofa in front of a wide coffee table, filled to its Mid-Century edges with trinkets, monographs, objects in heavy chrome — knick-knacks, baubles, curios. A wooden desk — large, but not as though it’s making up for something — is topped with papers and notebooks and fountain pens and correspondence, and I’m sure I spot a print-out of Wikipedia’s list of French film directors, A-F or similar. If this were an avant-garde, rarefied escape room, and your task were to work out what the person who owned this office did for a living, you would be stuck in here all day. At least you’d have some decent reading.

So I ask Charles Finch, whose own Wikipedia page (printed out or otherwise) tells me, rather limitingly, that he’s a ‘businessman and film producer’, what it is precisely he says he does for a living.

“I love Labradors and I love fishing,” he says, before acknowledging that “it is confusing – even people who have worked with me for years find it hard to put a finger on what I do.”

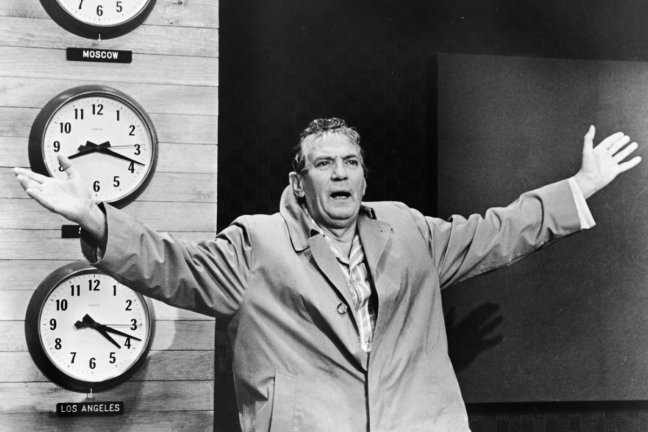

“I’m mad as hell,” Peter Finch [Charles’s Father] in his best known role, Network.

Jay Jopling, the White Cube impresario, once described him as a ‘polymath’ at a dinner they were hosting together at Harry’s Bar. This is a typical Charles Finch sentence: “And I kind of liked that. So, when I started being a polymath, by which I mean being in the movie business, being in publishing, and also building brands, then representing people for a while — all these kind of things — it was confusing, in the old days,” he says. “Now everyone does that. Your generation, they all want to be doing 10 different things. It was unheard of when I was starting out. Unless you had a discipline that people could identify you with in one sentence, you were considered a dilettante.”

This sort of plate-spinning is in the blood, however. “George Ingle Finch [Charles’s grandfather] was a mountaineer who climbed Everest in ’22 and invented the down-filled jacket and the portable oxygen cylinder,” says Charles. “He blew up a Zeppelin in the First World War from the trenches by firing off a mini-rocket. He also invented napalm. There’s lots of family speculation as to whether my father was really his son, but we choose to believe that there are enough bastards in the family, so we like to say he probably was.”

Charles’s father, meanwhile, was a man of singular, towering discipline: Peter Finch, the stage and screen titan who won more Academy Awards (five) for best actor than anybody else. Peter was a matinee idol in the Errol Flynn and Alec Guinness set, and in his later years settled in Jamaica with Charles’s mother. Charles spent the first few years of his life on the island, in a big house where they grew bananas and crops.

“It was difficult,” he says. “My father had disappeared and wasn’t present. My mother was amazing, but had a great friendship with rosé and champagne for many, many years that ultimately didn’t do her any good. It was not a conventional upbringing.”

Peter Finch is today best known for his role in Network, and specifically the denouement speech in the film in which his unravelling news anchor decries modern corporate media with the line, “I’m mad as hell, and I’m not going to take this anymore” — a thunderous epithet that grows more relevant by the year. Peter died before the film came out and won a posthumous Academy Award for the role.

“I hadn’t seen him for many years before he died. He wasn’t a very present father. The last time I saw him, I was five, and he died about nine years later. It was frustrating to always grow up as Peter Finch’s son, and yet never to have known him. At the same time, I used it wherever I could — whether trying to get into Hollywood or get a restaurant reservation.

“My mother ran out of money after that, and so I became a scholar at Gordonstoun. But it was kind of weird to have the name, and yet really to have nothing. It was a weird legacy to walk around with. I remember collecting quarters with my mother to try and have enough money to pay for food.”

Part of that mixed inheritance was a love of film. “I realised that what I really wanted to do was be a writer or actor or somehow in the movies. And so, I went to New York to study with Lee Strasberg [the founder of the prestigious Actors Studio theatre school]”.

“So, I went to Los Angeles. I was having a love affair with an Italian called Dialta, and she was also having an affair with Werner Herzog at the time.”

Charles waited at restaurant bars, where he realised there were decent tips to be had (as well as older women who might be enchanted by a fresh-faced English boy in a bow tie), and wrote films and plays in the daytime. A script or two got optioned, and soon Charles realised that the real action and money were in Hollywood. “So, I went to Los Angeles. I was having a love affair with an Italian called Dialta, and she was also having an affair with Werner Herzog at the time. And so I think she gave me the script [Herzog was working on], and I took that under my arm,” he says. “I went to Los Angeles to the Chateau Marmont, and got a job pretty much that night.”

This was the big dream: the Englishman at large in LA. “I was doing it — scratching my way up the tent pole,” he remembers. “I worked on Tim Burton’s first Batman. I wrote a script called Priceless Beauty and went on to direct and produce it. It wasn’t very good, but it was an amazing experience. From then on, I wrote another seven or eight movies, none particularly good,” he says.

“And then the last movie I made as a director… I was so broken-hearted with the reception it got at the Toronto Film Festival that I said ‘fuck it — I’m never doing this again’. And so I got a job with my agents, who happened to be William Morris.”

The film, released in 1996, was called Never Ever, and you can still find its trailer online if you dig around enough. (“That’s probably the best bit of it,” Charles jokes.) It’s a love story about an English investment banker in Paris. Charles wrote it, directed it and starred in it — and the damning reviews it got meant he “didn’t get out of bed for two weeks”.

“I couldn’t find anyone to be in the movie, and I got so fed up that I put myself in it, which wasn’t such a bad idea,” he says. “Maybe now I could do it, because I know more about what I’m doing. But in those days, I didn’t have enough experience, and it was too difficult a thing to do. I fell in love with Sandrine Bonnaire [his co-star], and she left me after the premiere when the reviews were bad. She’d deny that, but it’s a fact.

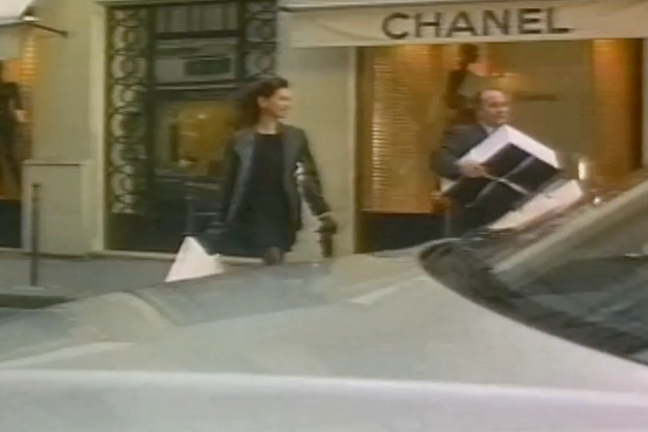

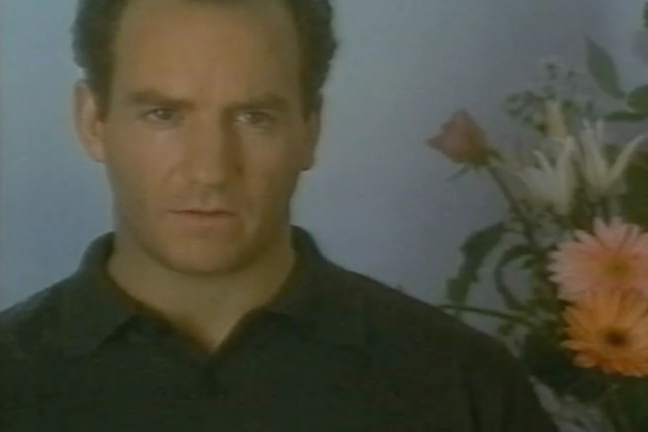

Stills from the 1996 film ‘Never Ever’, which Charles wrote, featured in and directed.

“It was devastating. Directing movies is the most fun thing I’ve ever done in my life. You paint a story with a camera. There is no better thing than that. I really loved it. So to give it up, because some motherfucker at Variety said my performance was ‘so flat you could land a jumbo jet on my head’ — it was devastating.”

Was it financially damaging too? “I never had any money. I always lived like a king, but I never had any money. So it wasn’t that,” he says. “It was just such a pure effort. It was beautifully made — a real love story and an attempt to do something different. But it’s just not a good film because I’m bad in it. If it had been somebody else, it would have been better. But then you get a review like that, and you don’t have the guidance of other people…” He trails off and shrugs.

Charles became an agent at William Morris, representing some of the biggest stars in town, a stable of more than 90 clients under his watch. “Malkovich was an amazing person to work with, and Willem Dafoe was incredible, and Cate Blanchett,” he says. “But it was a devastating fall, to go from being a screenwriter and actor and to go across the river, on the other side of everything, and start representing artists. It was truly a big leap that took many years to come back from. Many, many years.”

What was it like being an agent in Hollywood in the 1990s — an era before streaming, before the crash, before the internet really, the pompy moment of Ari Emmanuel and Chateau Marmont and the Vanity Fair Oscar Party actually being good?

“It used to be so much fun. It was So – Much – Fun,” Charles says. “Al Ruddy, my mentor, the producer of The Godfather and my dear friend who is 90 years old and still alive, used to take oxygen from a mask while smoking a fucking cigar. On the first meeting I had with Bob Evans [the renowned producer], he had a pyramid of cocaine on his desk. I’m not a drug user, and I never have been. But it was pretty fun. Whereas today it’s a different game. People are fucking nervous about what they say, and it’s hard to get big movies made unless they’re Marvel.”

Charles Finch with Lisa Love and Anne Hathaway at the Chanel and Charles Finch Pre-Oscar dinner 2014

"Directing movies is the most fun thing I’ve ever done in my life. You paint a story with a camera. There is no better thing than that. I really loved it."

Charles’s most lasting contributions to the good life have possibly been his pre-Oscars and pre-Bafta parties, which he’s been hosting since the early 1990s in LA and London respectively. They are some of the most coveted invitations in the anxious, sharp-elbowed movie-land calendar — chummy minglings of huge stars, arch string-pullers and people Charles simply thinks are interesting or good company. “But I find it pretty intense,” he says. “I’m not a party person, so it’s a funny thing that I’m well known for these two parties. I do tend to leave quite early. I’m a bookworm.”

Have there ever been any particularly tricky moments?

“I would say I’m pretty strong about bad behaviour, and I think people know that. There are lots of difficult things. Funnily enough, bigger stars behave really, really well. Tom Cruise, if he’s going to come, he’s coming, and he’ll come in the back door and say hello and be absolutely charming. Leo, if he’s going to come, he’ll be great. Ben Affleck, too.” But sometimes things “go crazy”, he says, and the smaller stars can often be tricky. Those that drop out on the night are particularly irksome: “‘Oh I can’t come because I’m lactating,’ they say. What the fuck is that!”

Most of the time, however, the parties are known for their sophistication and civility — little idylls of old-world glamour, as if camera phones have yet to be invented down in the swaddled depths of 5 Hertford Street. They are nice companion pieces to Charles’s latest project, A Rabbit’s Foot, which is a pleasingly old-fashioned and handsome magazine about films and filmmaking and film culture. The people that populate Charles’s parties pop up in bylines and portraits in A Rabbit’s Foot, which lends it the cosy, jolly, informed air of a scene writing about itself.

Copies of the magazine dot the office, alongside ephemera from other tangents and careers — like Chucs, the exquisitely branded series of London restaurants which Charles set up (the interiors – all Slim Aarons imagery and navy piping and walnut woods – are based on the inside of his beloved boat, Gael). Or Dean & DeLuca, the now-deceased upmarket deli chain which Charles was global chairman of for a while. On a wall by the sofa, there’s a collage of cut-out logos for another venture of some sort that Charles is about to launch — perhaps a style brand or a restaurant or both, somehow. All this, plus the day-to-day work of Finch + Partners, the strategic brand development and investment advisory that connects and underpins all of these worlds.

I ask Charles if there are any itches that he has not yet scratched. “I can see myself making another movie actually,” he says. “A fiction. Even if it’s 10 minutes long. I yearn to do that again.”

Is that to absolve what he feels might have been the failure of Never Ever, I say? “Maybe!”

Will he act in it? “No. I don’t think so. It depends on the story. Although I’m game to try anything again,” he says, and his eyes flicker with conspiratorial mischief. It would certainly be a pleasing third-act twist for Charles — a riposte to those nineties critics and another contribution to an industry he has loved from many angles. A fitting use, a nice echo, of the double-edged legacy his father left him, too, perhaps.

“I wish that, had I had a father, and after my third film, someone had said: ‘listen: there are bad reviews and there are good reviews — you must keep going,’” he says. “Because I probably would have kept making movies as a filmmaker. Now, I have no regrets. But I think that when that does happen to clients of mine, I now say: ‘listen, this is a piece of paper. You need to learn that some things were maybe not well judged here’ — and use it as a lesson and a spur.”

And what about his advice for others? Those young men and women who might want to ‘work in the movies’, perhaps, or do the sort of things that get you this sort of office?

“I think it’s about trying to help young people get to the point of knowing what they really want to do, quickly. I think a lot of time is wasted in taking the wrong jobs,” he says.

“The second thing is working hard. I think the ones who make it are the ones who come in early and arrive late. Not everyone wants to do that.”

“And the only other thing I would say is: preparation is such an important thing, whether you’re climbing a mountain, or sailing, or making a movie. Preparation and thoughtfulness,” he says, leaning back at the big-enough desk in the lovely, lived-in office. “But, unfortunately, those aren’t things you learn until you’re older.”

This interview was taken from Gentleman’s Journal’s Summer 2023 issue. Read more about it here…

Become a Gentleman’s Journal member. Find out more here.

Become a Gentleman’s Journal Member?

Like the Gentleman’s Journal? Why not join the Clubhouse, a special kind of private club where members receive offers and experiences from hand-picked, premium brands. You will also receive invites to exclusive events, the quarterly print magazine delivered directly to your door and your own membership card.