It’s been more than half a century since Gilbert Prousch and George Passmore (or Gilbert & George to you) began making art together. Later this year, in fact, they’ll celebrate 50 years of their work with their own foundation — a celebration which will allow them to show the work, they claim, that the likes of the Tate will not.

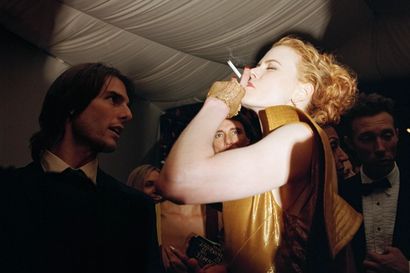

Best known for their large scale, multi-panelled, stained glass-like pieces (often depicting nudity, sex acts and bodily fluids or solids), George, 77, (left) and Gilbert, 75 have never really been a hit with the critics. That might be because their politics is at odds with the typical trendy leftiness of the British art scene — the duo describe themselves as “ordinary conservatives” — but it’s also due to the unabashedly uncompromising nature of their art.

Either way, the wider market adores them. Gilbert & George works frequently sell for more than £500,000 a pop. Not that the money really matters, of course. In fact, it’s the pair’s relationship with the man in the street, and their local Spitalfields stomping ground, that matters to them the most.

Here, they discuss the power of optimism, the danger of trendiness, and how the world has changed since the day they met at St Martin’s school of art in September 1967.

When we started out, people said: ‘It will never last.’ Now our biggest critics are all old or dead. Content and meaning in art still seem to be taboo. It’s still the big museums and institutions that decide what the trends are and it’s trendiness that makes us overlook the more interesting stuff. It’s like coming to London and going to the London Eye but not Darwin’s house.

There’s always been this gulf between critics and the public — there still is, not just in art, but in music and theatre.

Art has somehow separated from the real world. And although the world is an incredibly different place to what it was in 1967, I feel we’re still part of it. We’re dealing with disconcerting truths, but ones that are inside all of us. Of course we’re also different people today to who we were in, say, 1991. So we explore how we are today. Do we think more about our mortality now? Well, not as much as we think about the opposite. And I think you know what I mean…

The art world can be hostile to anyone doing anything different. But there’s always been this gulf between critics and the public — there still is, not just in art, but in music and theatre. We want our art to be visually powerful but also part of the world, which is why I think people tend to like our work. We’re optimistic about the west, whereas a lot of artists just moan about it. People want to thank us for that optimism.

Many people who stop us in the street — and this happens all the time — have never been to an art gallery. But the art speaks to them, because it’s about life. We get these half-dead teenagers on drugs coming up to us to tell us that their mums love our art. It’s very moving. We do everything ourselves. We make our art without any helpers, which is ridiculous. We plan and install all the shows.

The idea that our art is provocative is just a media invention. The public wants to be challenged. But art has in some way become separated from the real world. It’s the same with collectors. They like [our] art, but they don’t want it on their walls. But if they gave their cheque books to their children, they’d buy us.

So much of the art world exists in its own bubble. But we never really liked all those dinner parties. We’ve always kept to ourselves and I think our art is more modern for that. We see life in a different way because we don’t have friends, because we don’t go out. We’re able to be totally empty-headed. And we’re incredibly privileged in that way. It’s incredible freedom. We answer to no one but ourselves.

We see life in a different way because we don’t have friends, because we don’t go out. We’re able to be totally empty-headed.

For me as a solo artist I couldn’t have achieved what we have together [says Gilbert]. I just wouldn’t have had the energy to fight all the criticism — from the art world, from the media. We have so much public support now it doesn’t much matter, but I don’t like criticism. It is what it is. But no artist likes to be told they’re lousy.

We haven’t succeeded yet. We’re always hungry for more people to see and understand our art. Our legacy will be our work, all the negatives, the collections, the house. Our legacy is our life, and what we did. We only hope we did enough, fighting for that, I think. I want to protect everyone that I can.

Want more from the art world? Discover the timeless architecture of Ricardo Bofill…

Become a Gentleman’s Journal Member?

Like the Gentleman’s Journal? Why not join the Clubhouse, a special kind of private club where members receive offers and experiences from hand-picked, premium brands. You will also receive invites to exclusive events, the quarterly print magazine delivered directly to your door and your own membership card.