This story goes back a long way. I feel like a dinosaur when I tell it now. It was 1989, in Nairobi, and the head of the Kenyan Wildlife services, a man called Richard Leakey, was trying to solve the poaching problem in the country. Leakey wanted to send a strong message to the poachers of the world, so he decided to build a huge fire and put 20 tonnes of ivory on the top. It was a historic moment — it felt like something truly important was happening.

At the time I was at the French School in Nairobi, and I decided to go to the ivory bonfire with two friends of mine. We skipped Spanish class and pretended to be sick. I didn’t know it then, but that would be the first time I would meet Peter Beard. He was there taking photos for a magazine, and I knew who he was and decided to speak to him. At one point, he said: “you should come to my camp,” which was called Hog Ranch. It was on the outskirts of Nairobi, but it was like it was in the middle of nowhere, a tented camp in the wild — very eccentric and very bohemian.

Over the next few years I spent a lot of time at that camp, sitting around that fire. Peter’s place was like Andy Warhol’s Factory. Anybody who was anybody in the creative world — whether they were a writer, a journalist, a photographer, a model, or just someone looking for a mission in life — would drop by Peter’s camp.

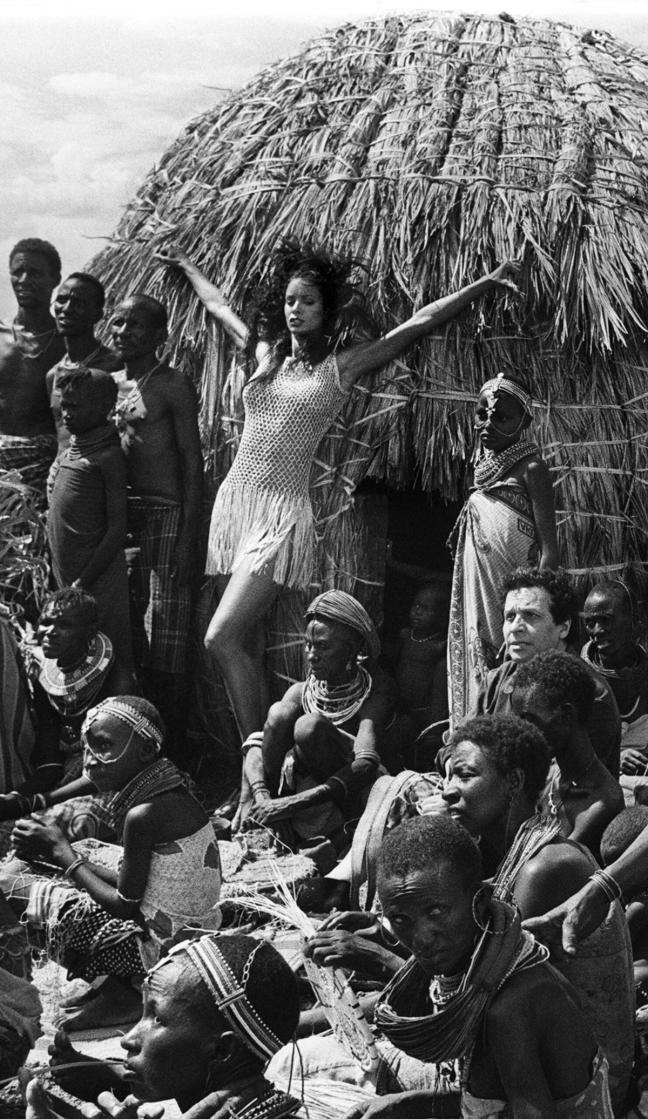

You would arrive at 6 o’clock in the evening for the first gin and tonic of the day. That was when the giraffes would come out, and they would eat just in front of you. Everyone would sit around the fire, exchanging stories about their last adventure or the next book they were writing, and if you were lucky you would arrive and there would be beautiful women at the party, too. Perhaps Peter would have just photographed them on assignment for an English or an American magazine, or they would simply be old friends dropping by to say hello.

Peter was one of those characters you meet very rarely in your lifetime. He was generous with his time, but the thing that really drove him was the demise of Africa, its wildlife, and its habitat. That’s what he wanted to talk about and that’s what kept him interested. He felt that Africa was the last show on earth — the last place where you could really experience something new out of something very old.

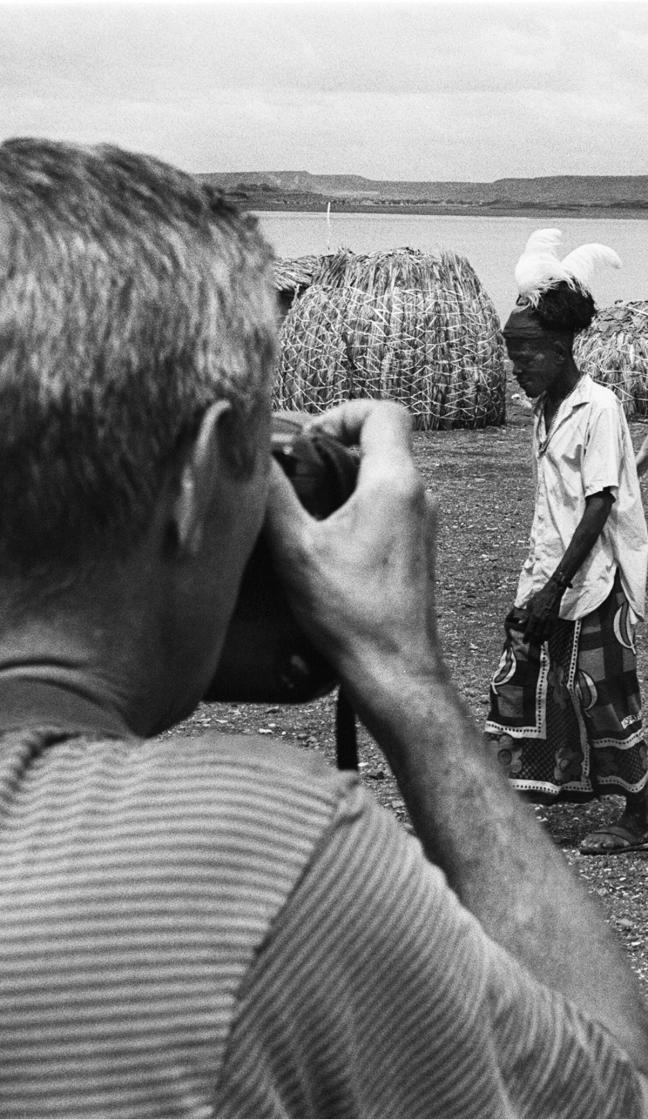

I was fascinated by Peter’s work and fascinated by him as a man. The End of the Game, the 1963 book that he had done on elephants still holds its own to this day, and he was ahead of his time on raising the issues that Africa, and Kenya, was facing. But his other work was interesting, too. I showed up one day in his camp. “Elle magazine is coming,” he said, “and we’re going to do this fashion shoot in Turkana. Why don’t you come along?”

Lake Turkana, for someone like me who grew up in Nairobi, was the last frontier. It is an incredibly remote place — I felt like I was going to the moon. I decided that I needed to do something different, and I knew I didn’t just want to tag along. So I borrowed a video camera from a friend, and I started to film the trip.

The clothes at the centre of the shoot were designed by Azzedine Alaia, the legendary French designer, and he wanted to come on the trip. It used to take you two or three days to get to Lake Turkana in those days, and when you got there they’d tell you that it has the highest concentration of Nile crocodiles anywhere in the world. It is infested, and dangerous, and it looks like the surface of the moon — but this is where Peter wanted to do his shoot. He had spent a number of years working on a book on crocodiles in the sixties, so he had been to Turkana many times before. Only this time he brought supermodels and Azzedine Alaia along in his luggage, too. I didn’t know it at the time, but that little video I took on that fashion shoot would carry on for the next few years, and turn into a film about Peter’s life across the world — from Nairobi to Paris to New York City.

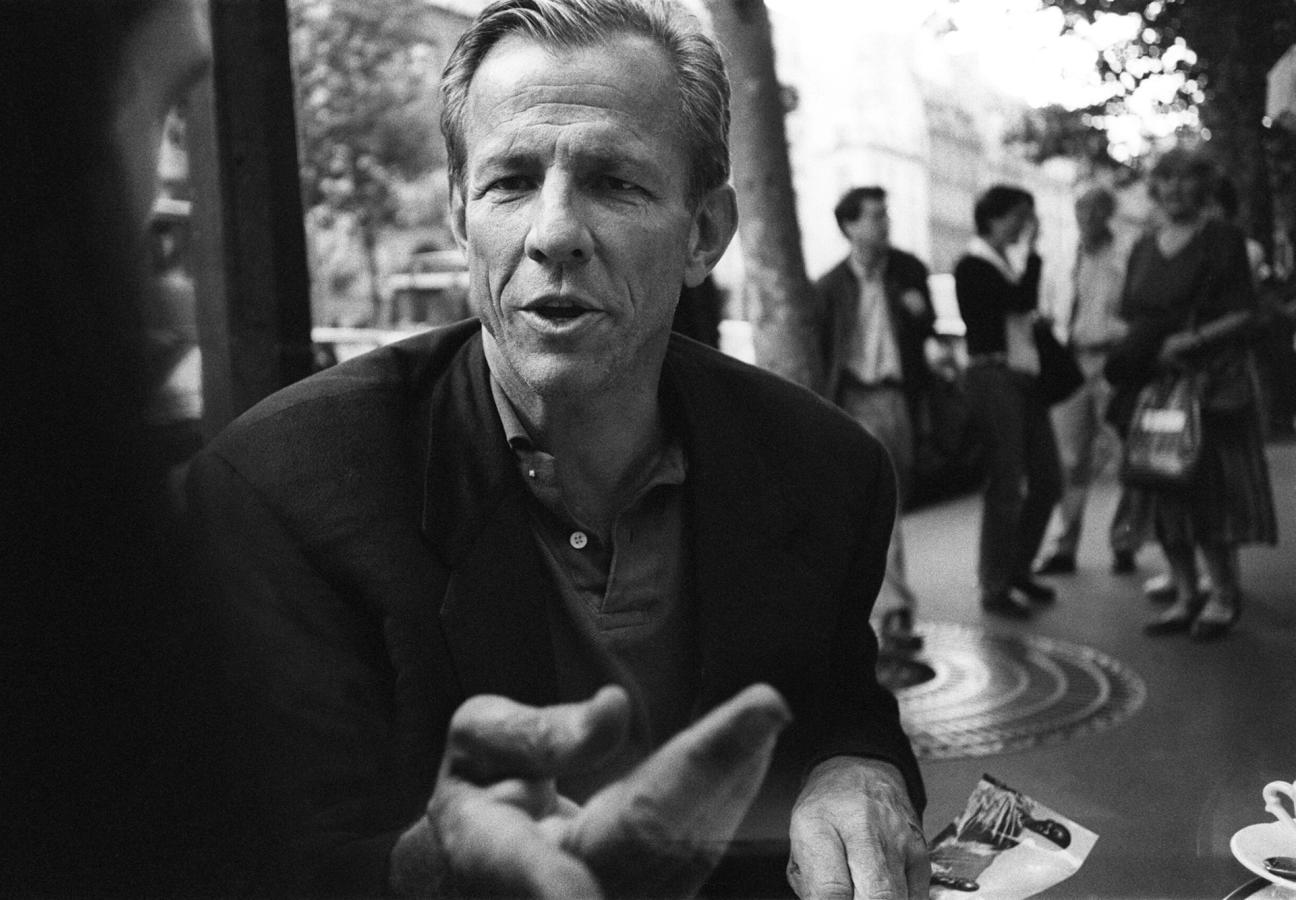

Everybody is celebrating Peter now, but in those days he was only really known by a certain circle — a happy few. You might call them the Jet Set now, but they were much more chic than that. No matter where you were in the world, Peter would have friends in high places, and he would meet them for a coffee, a cigarette, a lunch, a dinner, a party. He knew everyone, and everyone knew him. But he wasn’t famous.

Then came the accident that almost killed him. It happened in the Masai Mara Game Reserve, on the border of Kenya and Tanzania. Peter had gone there because the son of a very good friend of his — Calvin Cottar of the Cottar family, a famous Safari family in Kenya — had asked Peter if he wouldn’t mind coming to help in a photo shoot to promote a new camp. Peter went down to take some photographs and also play the model, and on one of the days of the shoot we spotted a herd of wild elephants. So we stopped the cars, stepped outside, and started walking towards the herd.

After a while, Peter and Calvin decided to get closer. They told us to stay back so as not to startle the elephants, but that they would keep going. And then, just as they were about 100 metres away, the wind turned, and the elephants spotted them. The matriarch, an old female bull, began to mock charge Peter and Calvin. She ran at them, making the most incredible noise, and then stopped. Usually, that’s a signal to say “now it’s time for you to go back” — and usually that’s where it ends. But that day was different. The matriarch suddenly began to charge for a second time, and we knew there was no turning back. Four more elephants joined the charge — and that’s when we all began to run.

Most of us managed to get to the cars, but Peter fell to the ground. We didn’t know at first whether he had made it, but when we looked out into the field we saw five elephants turning around and around, almost like they were in a circus — and we knew Peter would be in the middle of the group. I turned the camera back on and we rushed towards the herd, honking our horns and waving like crazy, and that’s when we realised what had happened.

"Peter was one of those characters you meet very rarely in your lifetime..."

Everything suddenly seemed so far away. We had a tiny VHF radio in our car, and we tried to find any frequency where someone might hear us. Eventually we got in touch with the flying doctors, and thank god for them — because when you are in the middle of nowhere, that’s the only way out and perhaps the only chance to survive.

Peter was in real pain, and we all suspected he had internal bleeding. I was speaking to him, and trying to calm him down, and letting him know that the plane was on the way. But Peter was very English about everything. As he was dying in front of us, he began to crack jokes. He said: “you mustn’t get walked on by elephants — it’s very inconvenient.”

The plane came in less than three hours, and within two hours of it arriving Peter was in Nairobi hospital. I was designated to go with him on the plane, and when we arrived I realised that I needed to push open the doors and scream and shout and grab the attention of anyone I could to tell them that this man was dying. Finally we got him onto a stretcher, and he went straight into the operating theatre. By that point Peter was fading, and by the time he arrived in the operating room he was gone and was only revived by electric shocks.

Bad news travels fast. Suddenly Peter was on the front of every newspaper across the world. Everyone was talking about him and they soon began to revisit his work, too, and it came at a very important moment for him — just as he was about to open his first retrospective at the Centre Nationale de Photographie in Paris. The accident happened in September 1996, and the show was in October. And Peter was there. He had come back from the dead.

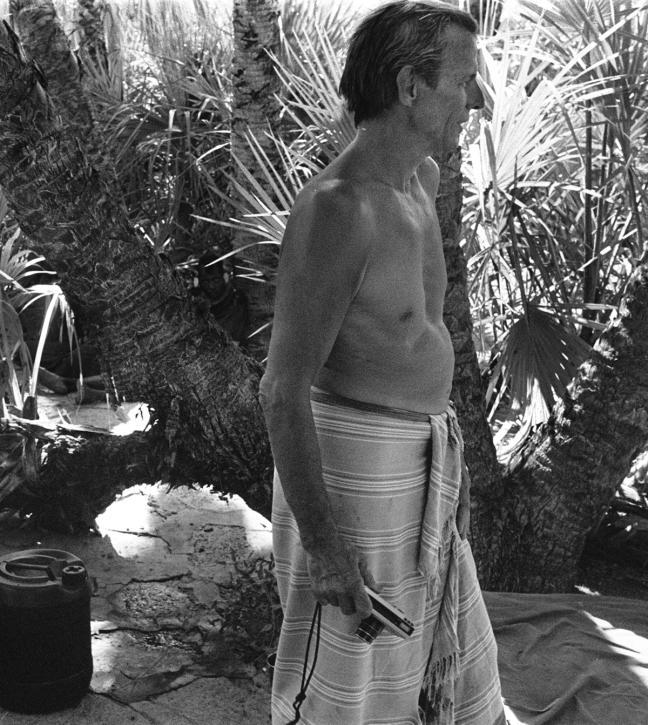

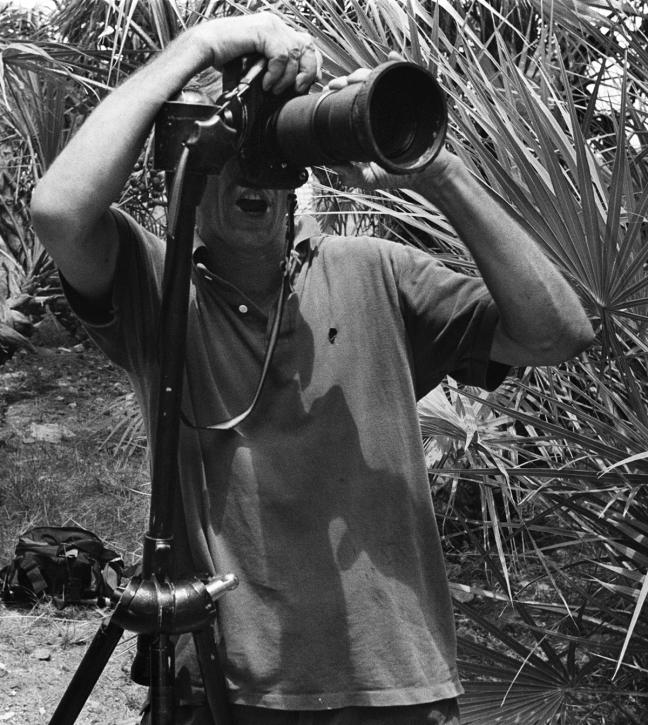

Peter was always testing life. I think his art demanded it. This was not the first time he had been charged by an elephant, and to get the reactions he did for the photographs he took, he had to get so close to the animals. Nobody took pictures like he did, and when you look at them now you almost feel like the elephant is on top of you. In that way he was a gladiator, a force of nature. He was interested in pushing the boundaries of life to their maximum. He wanted to see how life and death really tasted. To him, that was what Africa was really about.

I don’t think Peter was scared of anything. In many ways, he was like a victorian explorer. He was not a sentimental guy. If you’ve hurt yourself, stand up and walk, he would say. Get on with it — that was his philosophy. He didn’t have much time for whining or complaining. I think the only time he was depressed was when his first wife left him, and that was the last time he allowed himself any self pity. But the spiral of despair was so bad that he decided, I think, simply to never let himself feel that way again.

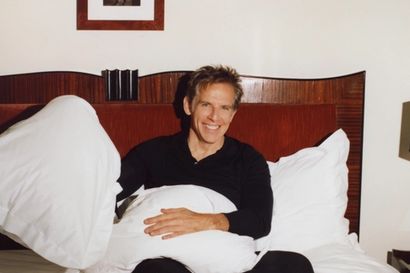

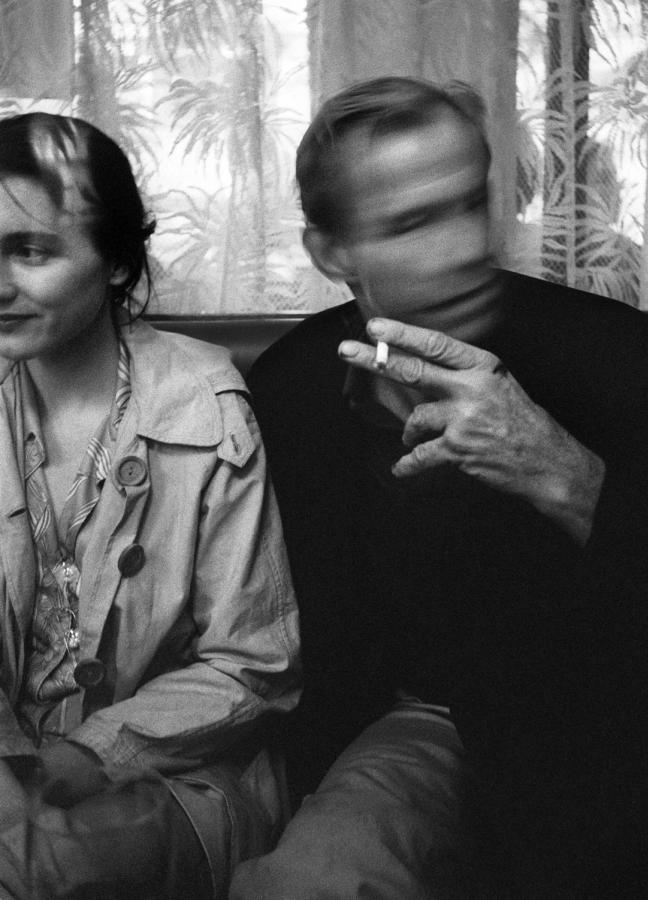

I knew two sides of Peter. Peter in private, which I saw very rarely, was a quiet and reflective man. He didn’t speak a lot. But Peter in public — in Paris, in New York — loved company and attention. It transformed him into “Peter Beard”, into something else entirely, and he would become the incredible storyteller that he was.

Peter liked living in both worlds — the primal place of life and death which Africa represents, and the silliness and fun of New York, Paris and London, with all those people who thought of him as “half Byron, half Tarzan,” as Bob Colacello put it. He knew that one side helped the other — that his personality would spread the word of his work. The accident brought something else to his aura, too, and everyone wanted a piece of Peter — particularly good looking women who wanted to be photographed by the man who had discovered the Somali model Imam. He didn’t mind that at all. He felt that wildlife was just about to disappear, and the only thing left that was interesting enough to photograph was the beauty of women. Maybe in some ways he saw them as gazelles, as giraffes, as embodiments of an elegance that could remind us who we are as a species.

Peter had the look of a movie star from the fifties. He was incredibly handsome, and nobody could say otherwise. He was very charming as well. He came from a very well-to-do family in America, but they held themselves and spoke like Anglo Saxons, with this undefined, very chic accent which was like English, but not quite. There was something about him that attracted people — his body language was generous, and he was curious and interested in others.

He would strike up conversations with strangers, and when we were in Paris we would sit at Le Cafe de Flore on the Boulevard St Germain and he would put his diary on the table, and everyone would see it and come over to take a look. He always wore the same afghan sandals, wherever he was, whether it was cold or hot, and he would wear them with the same khaki trousers and a blue formal jacket. You knew he was different from the moment he walked into the room.

I don’t know how he got away with it, but Peter never seemed to pay for anything. Sometimes he would give people pieces of his art to pay, and sometimes he seemed to just know people, or they knew him. He never had a penny, he never owned a wallet, and if he ever had a note in his pocket it would be gone in two minutes. So if you were going out to eat with Peter, you knew you would be paying the bill.

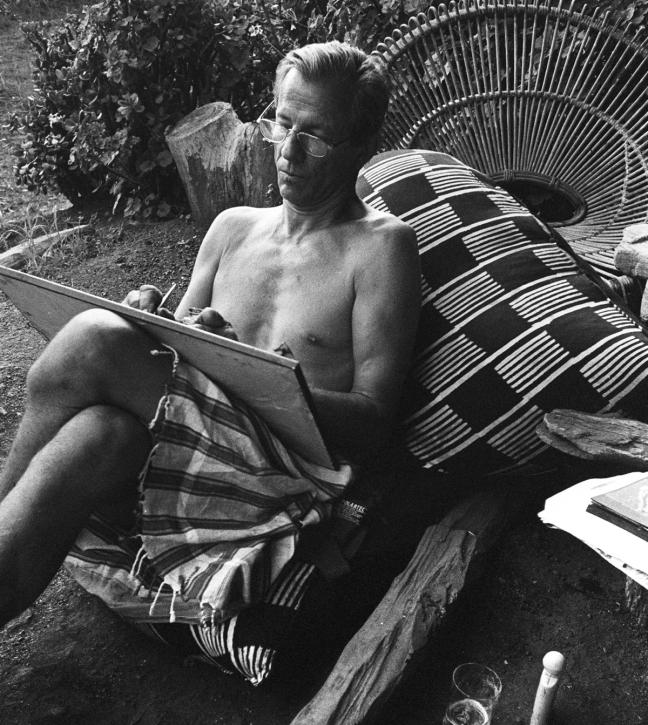

Peter didn’t have to work. He would be the first one to tell you that he was a dilettante. That’s a strong word, but Peter was somebody who had all the time in the world to do things well. For him, photography was a hobby, in the sense that it was done out of pure pleasure — it wasn’t based on the economics of life.

He couldn’t care less which camera he used or the technical aspects of photography. Peter knew that it doesn’t matter what equipment you own — it’s about the subject and what you are trying to say. You can describe a picture in any way — good, strong, interesting.

But to him, the one thing that you must never call it is ‘beautiful’. In the Peter Beard school, that doesn’t mean anything. Who cares, Peter would say. What’s important is the subject matter. It has to have depth and layers. If it’s too pretty, too fashion-y, too forced — then there’s nothing interesting left. You look at a pretty photograph and then you forget about it. Most of the time when Peter was shooting he took photos on portable point-and-shoot cameras that he could keep in his pocket. But the results were incredible. People would say “you must be shooting on a Leica.” But he didn’t, and he didn’t care.

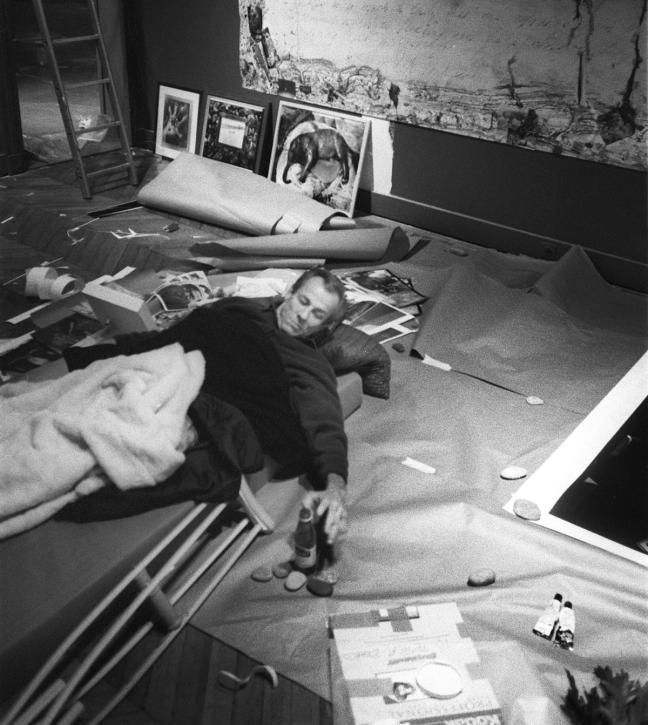

Francis Bacon relied on accidents in his work, and Peter was the same. He loved accidents, and he loved the idea that something might happen that he would not be in control of. For him, most of the time, those surprises would add to what he was trying to create. He was not vain in that way — he was carefree. He was not tied up by principles or rules. He would just let life flow, and he basically went against the norms of society and the modern mindset, where we all live in the future and constantly project our worries forward. Peter shared his philosophy with Africa in that way — the time is now, the day is today; let me connect with that and that alone. There’s a swahili saying that he liked: Sharwia mungu. It’s God’s affair. God will decide.

Bacon was probably secretly in love with Peter, and maybe not so secretly. They were very close. He connected with the work that Peter was doing, particularly with the carcasses and the dead elephants that Peter photographed. I think that spoke to Bacon’s work — they were both interested in the dialogue between life and death.

The last time I saw Peter was in 2008. I was incredibly affected by his death, in a way I didn’t expect. When I heard he was gone, I remembered a story he had told me in Paris, years ago. He said: “Guillaume, the best way to go, and to have people talk about you, is you go down to a beach, you leave your shoes, and you vanish.” That came back to me immediately. I thought he had gone for one last swim. I thought that he had done what all old elephant bulls do, when they step out of the herd, and they stay not far away, but they stay on their own, and they wait for the end. And then they found his body, in a tiny forest not far from his house, and I felt incredibly sad. I read the obituaries and the Instagram posts, and they all said that he died as he had lived — in nature, in the wild. But that felt odd to me. I didn’t feel that this was his last swim.

Peter Beard never did things in the normal way. His death was the same. Most of our lives end with a clear day of death, but we’ll never know what his is. In the West, we tend to die alone in our beds or in a hospital. In Africa, like in the animal kingdom, we die in mystery, in violence. It’s always brutal. In that way, Peter was true to Africa. But I don’t think he would think too much about it. “The chapter is closed, the page is turned,” he would say. Life carries on. “Tomorrow the sun will shine. Kwaheri kuonana. Goodbye and see you soon.”

David Yarrow on the making of his most famous photographs…

Become a Gentleman’s Journal member. Find out more here.

Become a Gentleman’s Journal Member?

Like the Gentleman’s Journal? Why not join the Clubhouse, a special kind of private club where members receive offers and experiences from hand-picked, premium brands. You will also receive invites to exclusive events, the quarterly print magazine delivered directly to your door and your own membership card.