Henry Lloyd-Hughes is the most famous actor you’ve never heard of. “Which is not, for the record, a bad place to be” he says. “But on hundreds of occasions I have been non-recognised. People think that they might have once sat next to me on a stag do or something, or that they know me from a wedding where I was on another table with the bride’s friends,” he laughs. “Which leaves me in a slightly awkward position. Because I don’t ever want to utter the immortal words: do you know who I am?”

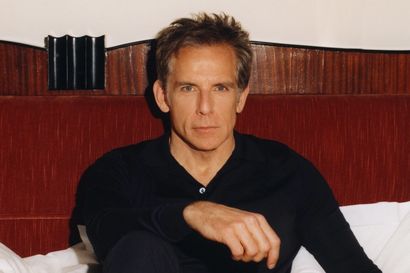

This is barefaced modesty if ever I’ve seen it. For young men of a certain generation — those, like me, whose teenage humiliations were pegged neatly to those of The Inbetweeners — Henry Lloyd-Hughes will always be recognisable as one Mark Donovan, the ruffian who haunts the four hopeless leads. (“I love him!” Henry says. “And I’d happily helm the spin off chronicles in a 25-part Netflix biopic…”) But you’ll also know him from The English Game (a chinny Alfred Lyttleton in an excellent moustache) or as the psychotic Aaron Peel in Killing Eve (dead-eyed tech founder in excellent glasses — those were his idea, by the way).

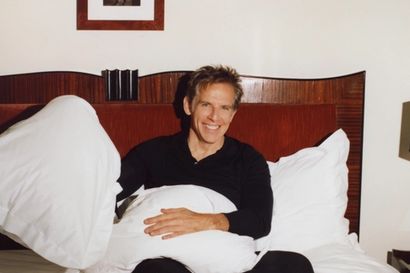

When we meet, in mid-February, Henry is in the middle of filming The Irregulars — a new Netflix blockbuster series where he stars as Sherlock Holmes in a dystopian version of Victorian London. Netflix! Sherlock Holmes! Surely this means he’s made it? “It’s an exciting pair of slippers to pull on. But also a bewildering set of slippers,” he says. (“And I haven’t yet been added to the WhatsApp group with Benedict and Robert Downey Jr…”) “But the gang of kids is the star. I am just the eccentric uncle. And I have been around long enough to know that there are so many variables that could affect this. I do not lie in bed at night thinking that tomorrow will be the day that I’ve finally made it.”

Nonetheless, there’s something in the water at Lloyd-Hughes Towers. Henry’s great grandfather was an on-set hairdresser back in the golden era of film. His grandfather was the wonderfully-named Basil Appleby — a stalwart of bygone omnibus shows with names like BBC Sunday-Night Theatre and ITV Television Playhouse. His mother, Lucy Appleby, was a film actress in the seventies. And his brother, Ben Lloyd-Hughes, is an actor too — he was in Skins (which is pretty much the anti-Inbetweeners), and War and Peace, and once played alongside Henry in a dramatisation of the life of the Miliband Brothers. Henry was even at nursery school with Phoebe Waller-Bridge (“which is now a bit like saying I was at nursery school with John Lennon”). The pair were briefly wed following a playground ceremony. But did he feel like he himself was destined for success? Like fame was always on the cards?

“Well, we all know that that is a fleeting and bewildering experience” he says. “And without wanting to sound too pretentious, it’s only the ‘work’ that stays after you’re gone…”

Work is the right word. Henry is no dilettante or dabbler. His first ever role was as a chap called Jenson Dawlish in Murphy’s Law — a troubled bad boy type on a houseboat. Henry went full method on young Dawlish, downing several litres of fake cider and smoking a dozen faux-spliffs — before vomiting enthusiastically all over his trailer. “I re-decorated the entire place,” he says. “And that was day one of my career. I really laid down a marker for mis-guided commitment. I’m sure there is a lesson there in not losing your marbles…

“But I can’t semi-commit. I’m trying to run a fashion company. I’ve got children that I need to parent. And a marriage that I need to be part of. So once I’m on set I’m truly one hundred percent committed.”

Professional actors are a bit like swans in this way. The calm, sleek exterior above the waterline conceals the frantic, exhausting work done below. This strikes me again as Henry breaks down the casting process in all its gory detail — that violent storm before the calm.

“I love being on set and making film and television. I feel a calling, as it were — without wanting to be too Jedi about it. But how you get there is a long and very convoluted process.”

Looks are the big part of it — even on the granular level of haircut, or moustache, or jawline, or side profile. “Nine times out of ten, the person who gets the job is the person who has just done that exact thing before — or the person who looks exactly like what they had in mind. Which can be disheartening,” he explains.

“And you just have to block that out, or focus on your technique — a bit like batting in a test match. When you’re an actor, and you are going up for big jobs and you aren’t getting them — that’s exactly the same as an opening batsman who keeps getting ducks,” he says. “I dig deep into all these sports psychology podcasts, because I think it’s so similar and so relevant to the job I do.

“But I’m really pleased to see my union is taking a front-footed approach in rolling out a clear mental health provision so people don’t get as rattled as I have been.”

Good manners might at least help. “I think that there’s an automatic power imbalance at play anyway. But it’s how you operate within that. By which I mean, in the same way that there is etiquette in dating and a good way of breaking up with someone, there should be an honourable way of saying to someone that they didn’t get the job. I have been in meetings with directors who have looked at me, teary-eyed, and said ‘the one thing I need to make this movie is you.’ And then you leave the room, and you never hear from them again. It’s moments like that that build up an unhealthy narrative of paranoia.”

Paranoia sounds about right. A few years ago, Henry got an unexpected call from a “huge American series” telling him he’d been cast in a starring role. This was it: the big break. Henry would have to drop everything, they said, and travel to LA first thing on the Monday. But when Monday rolled around, Henry’s agent discovered that the casting directors had made a huge mistake — they had meant to call a chap called Harry Hughes, not Henry Lloyd-Hughes. “Then they just screened my agent’s calls until he stopped ringing them,” Henry laughs. “The lack of accountability is pretty tricky.”

I imagine that why Henry takes such quiet joy in NE Blake, the clothing company he founded to make beautiful, functional, singular cricket whites. “No-one in the market was doing stuff that has the right feel — and feel is so much a part of it,” says Henry. “And having played club cricket for many, many years, and being an honorary kit man, I was always struggling to find the right stuff.” For which, read: high-waisted, double pleated trousers in drill cotton; popover shirts in white jersey cotton. It’s Ralph Lauren at the crease; C.B Fry with pinking shears.

It is beautifully niche. But it’s utterly sincere. “It comes from my great-great grandfather on my mother’s side, who ran a sports shop. So when my grandmother died, I inherited the whole archive of this business. And the whole thing just collided, and I thought: I’m out of excuses.

“Is it very labour intensive? Yes. Is it very stressful? Yes. Does it make me loads of money? No. But I will blindly march onwards. When I was working on the NE Blake dream, I said I just want to do it to know that I’ve done it. It’s not about stacking dollars,” he says. “It is a labour of love.” With Henry, you suspect it often is.

Want more from the world of acting? Mark Stanley explains why it’s time to stand up and find your voice…

Joint he Gentleman’s Journal Clubhouse here.

Become a Gentleman’s Journal Member?

Like the Gentleman’s Journal? Why not join the Clubhouse, a special kind of private club where members receive offers and experiences from hand-picked, premium brands. You will also receive invites to exclusive events, the quarterly print magazine delivered directly to your door and your own membership card.