Time to invest! The five luxury sectors that deserve your money

From Ferraris to firearms, these are the wisest buys

‘A thing of beauty is a joy forever,’ or so Keats was fond of reminding us. But the dead poet may have been more right than even he knew. For a new breed of investors, it isn’t the traditional instruments of bonds, futures and securities that are bringing renewed joy quarter after quarter – it’s investment pieces of an altogether prettier disposition.

To Thomaï Serdari, the Luxury Brand Strategist at Sotheby’s Institute of Art in New York, it all goes back to the recession of 2008. When the financial pillars so favoured by the investing class began to crumble to dust, its members started to look to luxury statement pieces to put their money to work. When they did, they sought out marques and names with a distinctive heritage and an air of authenticity, Serdari says – Gauguin not Goldman; Lafite not Lehman. At least this way, if it all comes to naught, the collectors have something nice to look at, or drive around in, or bring out at shooting weekends.

‘A thing of beauty is a joy forever,’ or so Keats was fond of reminding us

Fortunately for all involved, the luxury investment market has gone from strength to strength in recent years. With a newly minted class of Ultra-High-Net-Worths emerging from the wreckage of the financial crash, the appetite for craft pieces – and the pool of money – has grown deeper than ever. Now, alongside their oceans of liquid assets, the global mega-rich want something solid they can touch. Paintings regularly explode their auction estimates; wine bottles are assessed by quants with proprietary algorithms; Pateks are fought over like family estates.

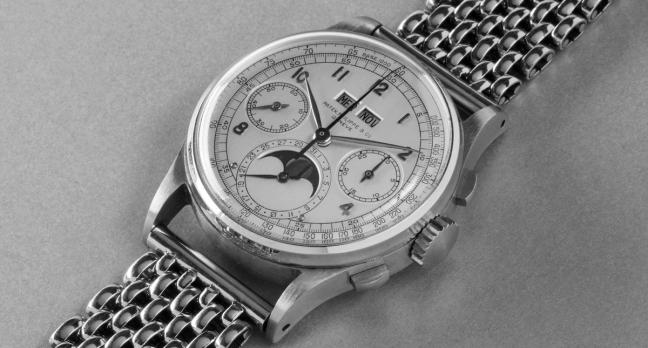

It’s not hard to see why. In November of last year, a 1943 Patek Philippe steel perpetual calendar chronograph went under the hammer for $11 million at a sale by Phillips in Geneva. The estimate was $3 million. As the most expensive wrist watch ever sold at auction, its sale vindicated what collectors have suspected for more than a decade: when it comes to Patek, time is money.

The mix of utility and appreciating value attracts investors to firearms. ‘More and more people are seeing luxury guns as a strong opportunity,’ says David Williams, director of Arms and Armour at Bonhams auction house. ‘The value of an investment usually comes down to two things: condition and quality of workmanship.’ It also helps, David tells me, if the item tells a story. ‘We’ve just sold a pair of duelling pistols made for Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas Thornton – he was an eccentric, a great sportsman and extremely rich.’

That backstory, he believes, helped push the sale to £67,250, a long way past the estimate. Other sale highlights include a Lloyds Patriotic Fund sword, valued at £100, which fetched £179,200 at auction, as well as a rare Colt Paterson No. 2 Belt Model percussion revolver, which raised a European auction record of £222,250.

Rarities aside, it’s still the great makers that present the most reliable returns, according to Williams: Manton, Ogden, Egg, Purdey, Holland & Holland. ‘Military guns are also consistently popular,’ he advises. ‘And I suspect flint and percussion long arms will continue to do a lively trade in coming years.’

In the world of watch investment, there are two names worth considering, if historic markets are anything to go by: Patek Philippe and Rolex. At the more affordable end of the spectrum (£3,000 to £8,000), Rolex makes watches that hold their value well, and very often appreciate over time. A lot of that comes down to recognition, both of the brand and of its individual models. Rolex has historically kept their product line small, limiting it to a few household names.

There are two names worth considering: Patek Philippe and Rolex

But not all Rolexes are created equal. The models that accrue the most value are the sporting issues: the Daytona, the GMT and the Submariner. But it’s also worth looking into Tudor, Rolex’s ‘working man’ sister imprint, which has just made its first forays into the UK market for several decades. Last year’s limited edition Tudor Black Bay (£2,330) is tipped for particular re-sale value.

To maximise returns, opt for vintage pieces that tell a story, such as the 1960s Rolex 5512s, for example – the first Submariner with the iconic crown guard. On a model like that, an investor could feasibly see their investment bulk by nearly 70 per cent in just 10 years, according to the Knight Frank Luxury Investment Index. They’d also have a design icon to wear every day in the meantime.

‘There’s been a trend in the last 10 years of traditional investors turning to wine as a serious proposition,’ says Hugo Thompson, Senior Wine Advisor at Berry Bros & Rudd. ‘The old rule was you buy two cases and you drink one and sell the other. Now investors are treating wine like an asset class in its own right.

‘When we’re putting together a portfolio, we suggest around 50 to 70 per cent Bordeaux, with the bulk of those being blue chip names [Château Palmer, Lafite Rothschild, Latour, Pichon-Longueville],’ Thompson explains. ‘The rest is a mix of red Burgundy, Champagne, Northern Italian reds and some bits from the Rhône.’

The wine investment market has produced remarkably steady returns over the past decade. ‘The Asian interest in fine wine has helped a great deal,’ Thompson says, ‘and in India alone there’s a compound growth of consumption of 30 per cent a year. As that consumption goes up, so too, of course, does the wine’s value.

‘Red Burgundy is the vogue product at the moment. Burgundy productions are tiny compared to those of Bordeaux, so certain houses can increase significantly in value.’ Thompson notes the wines of Henri Jayer as having been good to their investors. ‘Henri sadly died in 2006. So now the supply has been curtailed and certain vintages have been put on a high pedestal.’ In 2015, Henri Jayer Richebourg Grand Cru was selling at an average bottle price of $15,195. It’s still rated as the most expensive wine in the world at global auction.

‘But my advice is always buy something you love to drink,’ says Thompson. ‘The investment will be sweeter if it pays off after that.’

The 20 most expensive classic cars ever sold at auction all came under the hammer in the last four years. Auction house Artcurial’s sale last year of a 1957 Ferrari 335s was significant not just for its near-$36 million hammer price, but also for the car’s appreciation by some 500 per cent across the preceding decade. This is a consistent theme: models defined by rarity, aesthetic brilliance, story (the 335s had set a lap record at Le Mans and was driven by Stirling Moss) and nostalgia tend to adjust in value relatively little in their first one-to-five years, before leaping dramatically to often nearly five times their buying price after a decade.

The 1957 Ferrari 335s was significant for the car’s appreciation by some 500 per cent across the preceding decade

A Mark 1 Volkswagen Golf, for example, was all but worthless just 10 years ago. Now a good model is worth £15,000 and rising fast. Scarcity value has here been replaced by a sort of cult nostalgia of the early 1980s.

‘The key is being selective,’ says Paul Michaels of Hexagon Classics in South Kensington. ‘Those with full histories in exceptional condition, either completely restored or lovingly maintained with some age-related patina, will always command the highest prices.’

Michaels estimates the market will rise by eight per cent in the next three years. That is conservative: the general market consensus is closer to 15 per cent. Though the storage and maintenance for some models might effectively eradicate that increase, for less delicate models it represents a reliable return on investment.

‘The first thing we always advise is buy something you’re happy to have on your wall for the next 10 years,’ says Alex Dolman, Associate Specialist in 20th Century and Contemporary Art at Phillips. ‘Art, perhaps more than any other investment class, has a personal appeal.’

This makes it tricky to second-guess the future movements of the market. If a small but powerful cabal of gallery owners decides to inflate the market around the pieces they represent, they can effectively pump and dump the artist like stock in a company. ‘Several contemporary West Coast artists saw their pieces rise from about $10,000 to $100,000 each in the space of five years. The prices peaked in 2014, and now they’re back down at $10,000 again.’

Dolman estimates the markets tend to move in cycles of about seven years. ‘At the moment we’re coming out of the bottom of the cycle.’ As the bubble begins to inflate again, it is post-war European pieces that represent ‘a good market to be in’. He cites artists such as Gerhard Richter and Sigmar Polke as interesting bets.

Adrian Ghenie, a Romanian artist specialising in autobiographical paintings, is the modern poster boy for art-as-investment. His works were trading in 2013 at between £5,000 and £20,000 a piece. In October 2016, his 2008 work Nickelodeon went for £6.2 million before fees – four times above its estimate of £1.5 million.

Become a Gentleman’s Journal Member?

Like the Gentleman’s Journal? Why not join the Clubhouse, a special kind of private club where members receive offers and experiences from hand-picked, premium brands. You will also receive invites to exclusive events, the quarterly print magazine delivered directly to your door and your own membership card.