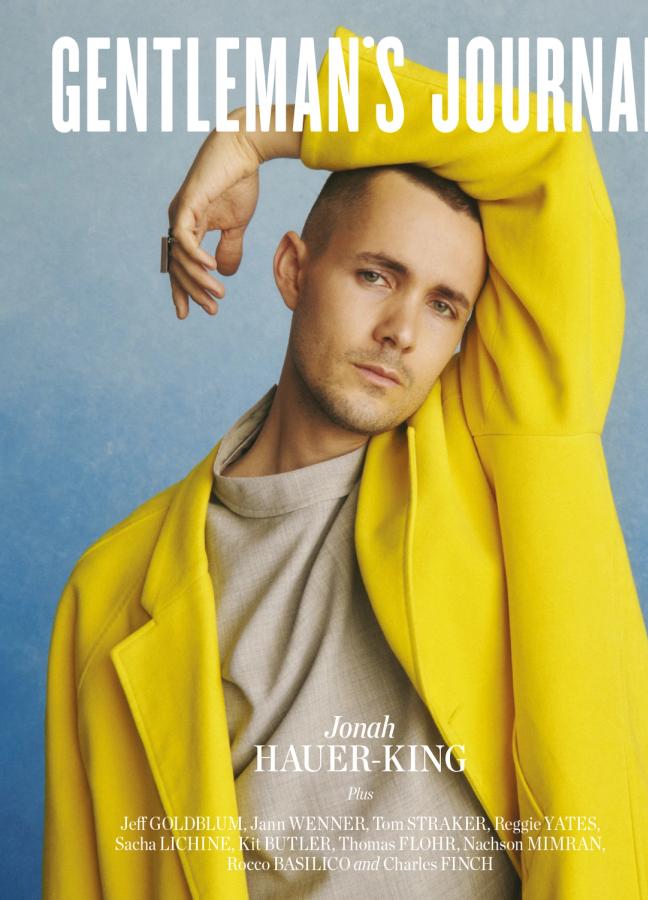

The Little Mermaid’s Jonah Hauer-King is riding the wave

Going straight from playing Prince Eric in Disney’s new re-make of the classic cartoon, to a leading role in Sky’s upcoming TV adaptation of The Tattooist of Auschwitz, it’s no wonder Jonah Hauer-King is on the verge of an identity crisis. But, despite his seemingly recent rise to stardom, 10 years of ups and downs precede his new-found fame, and he’s taking everything in his stride

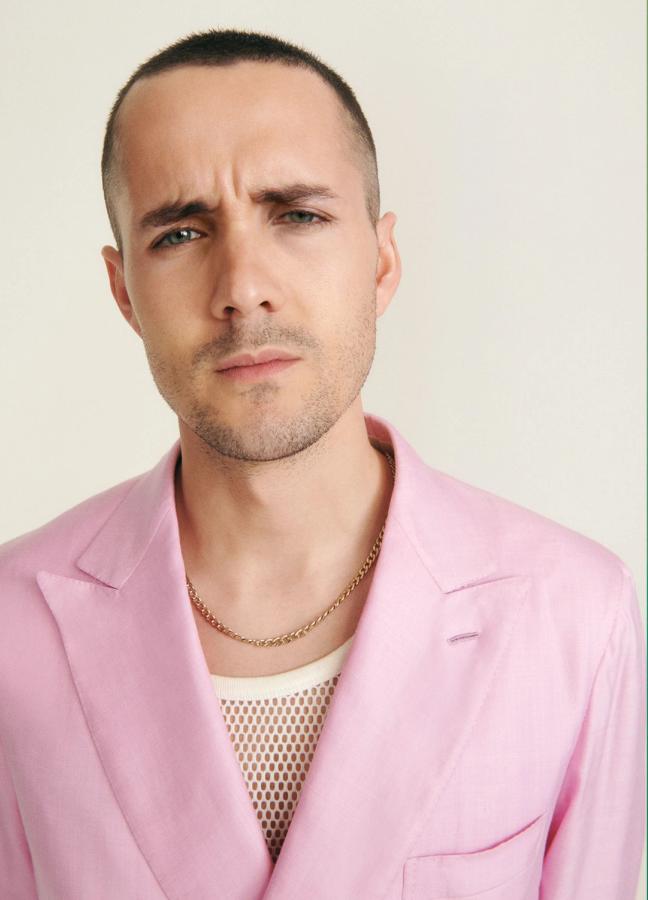

I hope he won’t be offended, but the Jonah Hauer-King who wanders into the East London studio where his picture is to be taken for Gentleman’s Journal does not look much like a fairytale prince.

In May, the actor announced himself to the world with a starring role as Prince Eric in Disney’s live-action re-make of The Little Mermaid. Eric is buff and strong, with a lush head of dark hair – the kind of beefcake any mermaid would be drawn to. Hauer-King, by contrast – handsome chap though he is – is thin to the point of gauntness, with a shaven head that has only just returned to the level of tennis-ball fluff.

“I’ve been in Slovakia for four months filming The Tattooist of Auschwitz,” the 27-year-old explains, a tad apologetically, running a hand over the head. Hauer-King is playing the title role in Sky’s six-part TV adaptation of Heather Morris’s 2018 novel, which sold more than three million copies. Based on fact, it tells the story of Slovakian Jew Lale, who is employed as a tattooist in Auschwitz, thinking it is simply a factory, and falls in love with a woman he is tattooing.

DIOR COAT, £2,500; top, £1,500; KILT WITH BELT, £2,700; TROUSERS, £1,000, dior.com; BOOTS, stylist’s own

“It was easily the most difficult job I’ve ever done, but also very formative and rewarding,” Hauer-King explains. “There was an amazing atmosphere on set, a solidarity between people feeling they were telling an important story that needed to be told. We wanted to make sure we did that life justice.”

The gig was also difficult in a practical sense, because it required Hauer-King – who had bulked up to the size of a prince who, he says, “looked like he had spent his life swinging around on ropes” – to slim down dramatically. There are 20 kilos between his extremes of weight.

“It’s strange being thrust into the press for The Little Mermaid,” he says. “I’m having a bit of an identity crisis. I don’t recognise The Little Mermaid version of myself and I don’t recognise this version of myself. The real me is somewhere in between. But I don’t really know any more.”

To help with the weight loss, he employed the services of a nutritionist, Steve Grant, who specialises in films about prisoners. “It was just about having an unhealthy level of control over what you put into your body,” Hauer-King says. “Basically, just white fish and steamed vegetables, and no going out to restaurants.” That was a particular wrench because restaurants are his favourite thing to do, and since he got back he has been on a spree.

“I’ve been on a grand tour,” he says. “I went to St John, Dorian, the Parakeet, Sam’s Cafe in Primrose Hill. I’ve been around.” He licks his lips slightly at the thought, like an inmate released.

The Tattooist of Auschwitz is scheduled for release later this year, and will surely win Hauer-King plaudits for his range. For now, though, there’s The Little Mermaid, which came out four years after Hauer-King was originally cast, in a very different, post-pandemic world. In the 1989 original cartoon, Prince Eric is – forgive the expression – somewhat two-dimensional: the wide-eyed but dashing heir to a seaside kingdom, who falls in love with the mermaid who saves his life after a storm.

BRIONI JACKET, £4,680, brioni.com; VEST AND JEWELLERY, stylist’s own

“I was trying to get to know him a bit better,” Hauer-King says. “Eric is an iconic Disney figure, but we didn’t know that much about him and who he was. He was a charming prince, and that was great, but for a live-action contemporary version you want a slightly more four-dimensional character. We gave him a more interesting and complicated back story, and tried to understand a bit more about him and what he wants from life, his frustrations. Partly it was for him, but it also means his love story with Ariel feels more earned. They’re both trapped in castles, looking outwards.”

While he might not be heir to a seaside empire, in real life Hauer-King is a scion of a different kind of kingdom. He has hospitality in the blood. He was born in 1995, the youngest of three children — he has two older sisters — to Debra Hauer, an American psychotherapist, and the restaurateur Jeremy King, one half of Corbin and King, the duo that gave London The Wolseley, Brasserie Zédel, The Delaunay, Fischer’s, Soutine and Colbert. The Wolseley was Lucian Freud’s favourite restaurant. A A Gill wrote a book about spending all day there. King Senior presided over them with patrician grace until last spring, when he and Chris Corbin, his business partner, were ousted from their own restaurants by the other main shareholder, the Thai-based Minor group. I tell Jonah that I last saw his father the day he announced his departure, and he looked like a man who had suffered a death in the family.

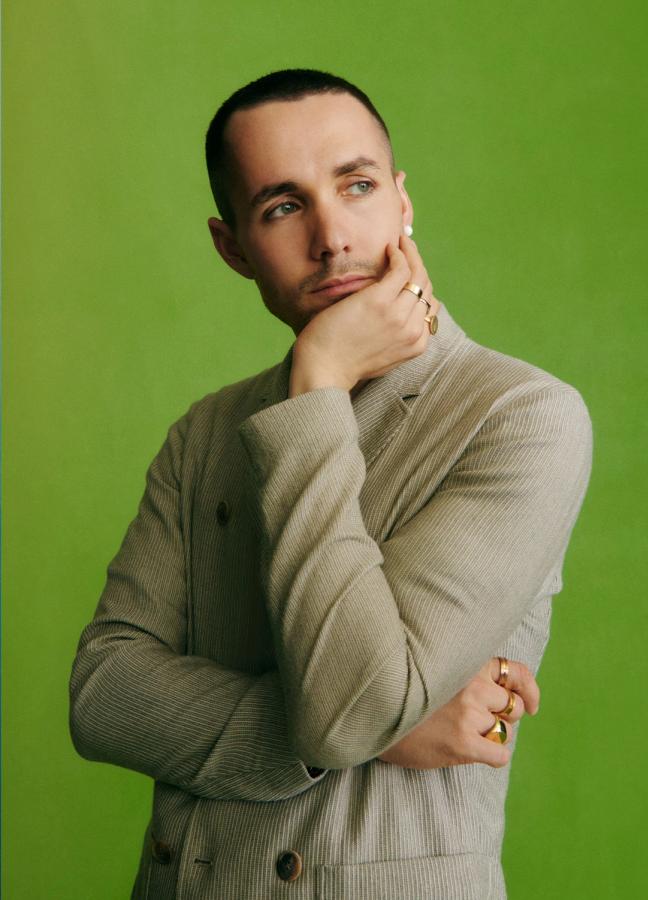

GIORGIO ARMANI JACKET, £ 1,900, armani.com; JEWELLERY, stylist’s own

“I think it was like that,” Hauer-King says. “Despite his success, he always ran them like family-run restaurants. He poured so much of himself into each one, so much creativity, that having them taken away was just devastating. But he’s okay. He’s scheming.”

If acting wasn’t in the blood, then acting-adjacent businesses were. Debra had worked in the theatre, and psychotherapy, in as much as it is about understanding and empathy with different states of mind, is not a million miles from acting. A dinner service is something of a performance, too. “The old man always said that his restaurants were a bit like a stage, and they were theatre in the sense that they were immersive experiences about atmosphere and excitement.”

“I’m having a bit of an identity crisis. I don’t recognise The Little Mermaid version of myself and I don’t recognise this version of myself”

But while he did plays from an early age, Hauer-King was not one of those born-to-it thespian prodigies. It wasn’t until sixth form at Eton that he took a friend’s play up to the Edinburgh Festival Fringe and caught the bug. “I loved being part of the company, of being part of Edinburgh, flyering every day, going out at night. It was exciting.” Back at school, he started doing every play he could and met an agent, who took a punt on a schoolboy with no professional experience. He decided not to go to university in the hopes of making it as an actor.

“I was very excited about getting an agent and just wanted to be an actor,” he says. “It took six months of auditioning and not getting anywhere, and waiting tables at Zédel before I realised that it was an incredibly precarious up-and-down industry. I got cold feet and decided to apply to university. I thought I would do that, put the acting on ice, and see what happens.”

University, in the breezy way of the bright North London elite, was theology at St John’s College, Cambridge. “It gave me breathing space, so I had other stuff to talk about in auditions.” The professional parts followed, but not at the expense of a first class degree.

“There has rightly been a shift in trying to redress the ridiculous imbalance of how much privilege there is in the industry”

Is he conscious of coming from the private school-Cambridge production line that has given Britain so many of its leading actors in recent years? Is it even still an advantage, when the discussion about that kind of background, especially in the arts, is so fraught?

“For sure,” he says. “And anyone who says it isn’t is kidding themselves. That kind of privileged education is very unique, and gives you so much. There has rightly been a shift in trying to redress the ridiculous imbalance of how much privilege there is in the industry and inaccessibility and how much the roles and casting had shifted to one sector of society. When I turn on the TV, I’m still seeing a lot of white dudes, and still seeing a lot of guys from very privileged backgrounds. I don’t think those roles aren’t there for them.”

There’s another advantage of going from The Little Mermaid to The Tattooist of Auschwitz: it helps head off any perception that he is a posh one-trick pony. “I’m looking for different things to be asked of me,” he says. “I only did it intentionally in as much as I knew they would be different experiences. That felt exciting because I knew I would be challenging myself in different ways. If it makes me feel nervous about the prospect of doing it, that seems like a good reason to go for it.”

LOUIS VUITTON JACKET, £2,700; SHIRT, £805; TIE, £1,120, louisvuitton.com

Beyond work, Hauer-King is a long-suffering and season-ticket-holding Arsenal fan, having grown up within shouting distance of Highbury and the Emirates, where he sits with a friend he has known since he was two. “I hope we’re still doing it in 50 years,” he says. At the time of writing, a promising season for The Gunners has started to fall apart.

“I take credit for it,” he jokes. “Since I went away to Slovakia, things have started slowly to go wrong. It must be because they can’t hear me singing.”

While he seems level-headed for someone being thrust into the spotlight, he is not above allowing himself to enjoy some of the trappings of his new situation.

“I’ve been introduced to a side of fashion I didn’t know about. I’ve been learning about how you tell stories through fashion, how you express different sides to you”

“I didn’t think I was a clothes guy until recently when I’ve been dressed for things, working with stylist Chris Brown,” he says. “I have loved it! I’ve been introduced to a side of fashion I didn’t know about. I’ve been learning about how you tell stories through fashion, how you express different sides to you. I know you do that unconsciously, but I wasn’t aware of it. I love classic tailoring – double-breasted three-piece suits – but I am also wearing a custom-made jumpsuit, which feels like a different part of me. It’s hard to articulate, but it feels like it embodies different parts of you.”

There are other projects in the works that he can’t yet talk about, although he hints excitedly at something to do with horses and swords. For now, though, Hauer-King has to focus on doing justice to a remake of one of the most beloved cartoons of all time. Although he’s worked fairly consistently, there hasn’t been a part with anything like the same budget, profile or reputation. Get it right and he might be a generational heartthrob; get it wrong and he’ll be back to auditions. He doesn’t seem like he’ll be fazed either way. The price of getting an agent at 18 is that if you are still waiting at 27, it feels like a long time. “That agent is finally seeing some reward,” he laughs, “they’ve had 10 years of ups and downs.”

If he is circumspect about the possibility of imminent celebrity, it might be down to his theological training. But equally it could be because, while he seems to the outside world like an overnight success, he has been working at it for a while.

“I try not to overthink it,” he says. “People keep telling me that this or that will change. But I’ve had experiences before where people have said it would change and it hasn’t. You become quite sage about that kind of chat. I accept this might be different. It only makes me feel daunted because I am just about old enough to have a fairly grounded and stable life. I have a relationship, my friends, my life in London. I find the idea of that changing quite daunting, so I pretend it’s not going to happen.”

Whatever the fate of the prince, it seems likely the young Hauer-King will be able to handle it.

This feature was taken from Gentleman’s Journal’s Summer 2023 issue. Read more about it here…

Become a Gentleman’s Journal member. Find out more here.

Become a Gentleman’s Journal Member?

Like the Gentleman’s Journal? Why not join the Clubhouse, a special kind of private club where members receive offers and experiences from hand-picked, premium brands. You will also receive invites to exclusive events, the quarterly print magazine delivered directly to your door and your own membership card.