Tony Fitzjohn has mistaken me for somebody else. “Are you calling about the aeroplane parts?,” he says, his languid, gravelled voice crackling down a phone line from somewhere in the Kenyan bush.

This is not a question I’m asked particularly often (though it is tempting to keep up the act for just a moment, and speak in manly tones, as an equal, of fuselages and manifolds.) But it’s one of the more mundane sentences Fitzjohn will utter this morning, or on any given morning at any time in the past 50 years.

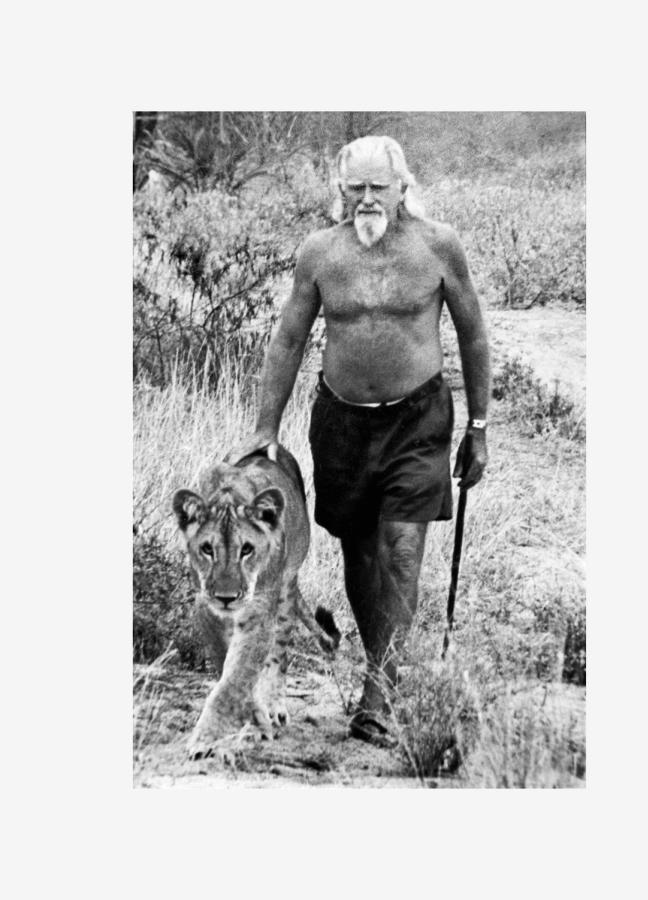

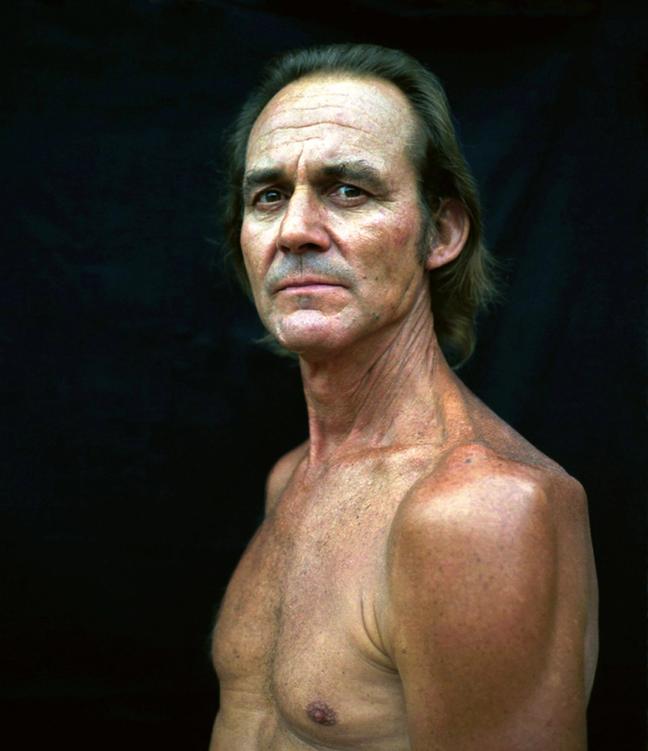

The conservationist — though that buzzword can barely contain him — has lived a life of almost unthinkable adventure. His biography — and his character, and his sweeping hair and his gruff handsomeness — seem plucked straight from fiction, or a long-dead era, or both. A lost Tarzan with the cut of a mid-century racing driver; a man who, with bare hands, a Land Rover, and a stinking hangover, built one of the most remarkable national parks in Eastern Africa.

The only problem with a story of this persuasion is that you find yourself straining constantly to avoid the obvious cliches, which pop up like potholes on some wilderness track. So I’ll get them out of the way right now, at the start, for you to use as you see fit: the lion-hearted, leonine lion king, walking nonchalantly through the lion’s den. The wild card: wild at heart, born to be wild.

Half a century ago, a 24-year-old Tony Fitzjohn pitched up on the African continent, a refugee from suburban North London. He surfed a little, worked at nightclubs, partied, scuffled. Got arrested, at one point, for disarming a policeman of both his rifle and his dog (“I got in a bit of trouble for that,” he says, with truly English understatement.)

And then, soon enough, Fitzjohn bumped into Joy Adamson, the wife of the famous conservationist and lion whisperer George. She told him they might have some pick-up work going over at Kora National Park near the Tana River in Kenya. “George needs someone,” she said, in icy Austrian tones. “His previous assistant has just been killed by a lion.”

“I thought: sounds pretty good to me,” Fitzjohn, now 74, remembers. And then he was off — airdropped, almost literally, into the heart of Somali Kenya, and the overawing, barren infinity of the wild bushland. “And I just knew, right from that first night, that that was where I was meant to be.”

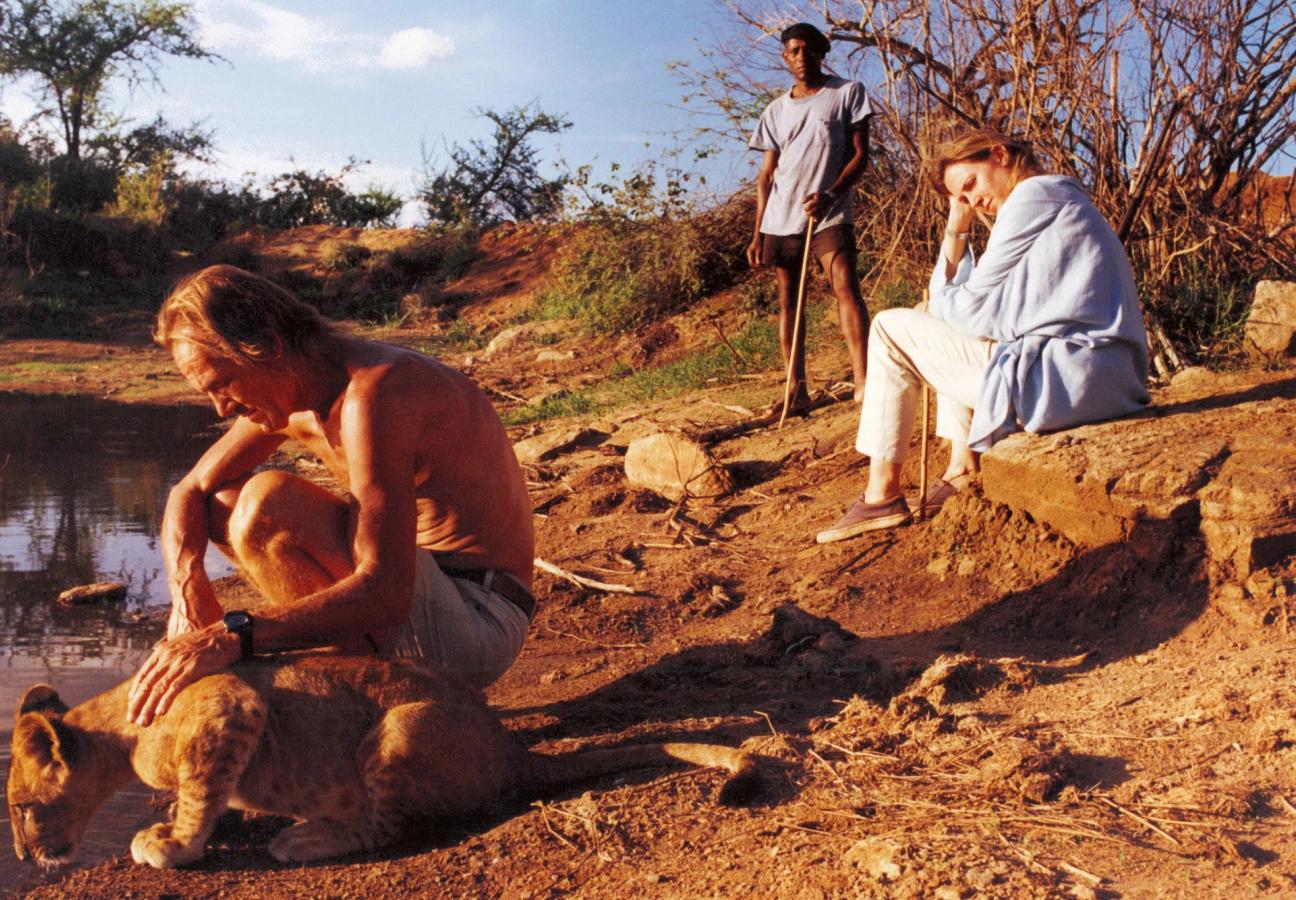

“George came out of the mess, with its sacking covered walls and palm leaf roof, and an old fashioned Tilley lamp hissing behind him, like a halo.” Fitzjohn begins. “He looked like an old testament prophet.” Adamson was already renowned, by then, as perhaps the most successful lion conservationist in Africa — “long before all that commercial, look-at-me stuff”, Fitzjohn adds — and his remarkable success in rehabilitating orphaned and rescued lions back into the wild had led to a book and a feature film on his life.

“But he was a very quiet man — not given to talking very much, very content with the life he’d led, and being with his animals. It was magic, the understanding that he had with those animals — the unspoken relationship he created,” Fitzjohn says. At one point early on, Adamson asked his young recruit how long he might stay for, expecting him to say a couple of months. “I don’t know George — 10 or 12 years?”, Fitzjohn replied.

“Here I am, quite a troubled child, quite a wild one. And I thought: this is where I want to be — this is what I want to do,” he says. “There was no money in it. I didn’t get a salary for the nearly 20 years I was with him. But I did it purely for the way of life, purely for the privilege of being on this planet and being able to do something like that — being able to pay your dues. I owed everything to George. Everything that’s okay about me today came from those years with him, and from his patience.”

“He looked like an old testament prophet...”

Life at Kora was one of overwhelming isolation. The camp was situated two days’ travel from the Kenyan capital of Nairobi, and conditions were basic. Aside from a few camp employees and George’s brother Terence, Adamson and Fitzjohn would go months at a time without being visited by an outsider. The work was everything.

“Our whole life was based around the lions: their health, their survival, their coping with going back to the wild. I became a self taught mechanic, and I learned to maintain all the vehicles. I would also do the supply trips to Garissa [the Somali Kenyan capital], though god knows why the bandits didn’t take me out,” Fitzjohn laughs.

“The police would get shot up, even the commissioner would get shot up. And there I was, a heathen, storming down with a beer in one hand and a joint in the other, the ghetto blaster booming. But they never touched me. I think there was someone up there looking after me. And I’ve always been prepared to take my chances for what I thought was worthwhile.”

Fitzjohn soon became Kora’s de facto PR man and fixer: dealing with the local authorities, talking to the police, keeping things cordial. “It mainly involved a lot of drinking in the police mess and the army mess in Garissa,” he says. “Drinking was a big part of life out there, I suppose, though not so much in the bush.”

At one point, Fitzjohn thought two policemen were trailing him through the city — so he hid in an alleyway and ambushed them, taking them both out with fists flailing. That afternoon, he discovered that they’d actually been sent to look over him and protect him, should anything turn nasty.

“So I had to go and apologise to them at the station. Well: that turned into a long night on the beers, didn’t it…” he says, slightly sheepishly. “It was the Wild West, in many ways. But the Wild West with Land Rovers.”

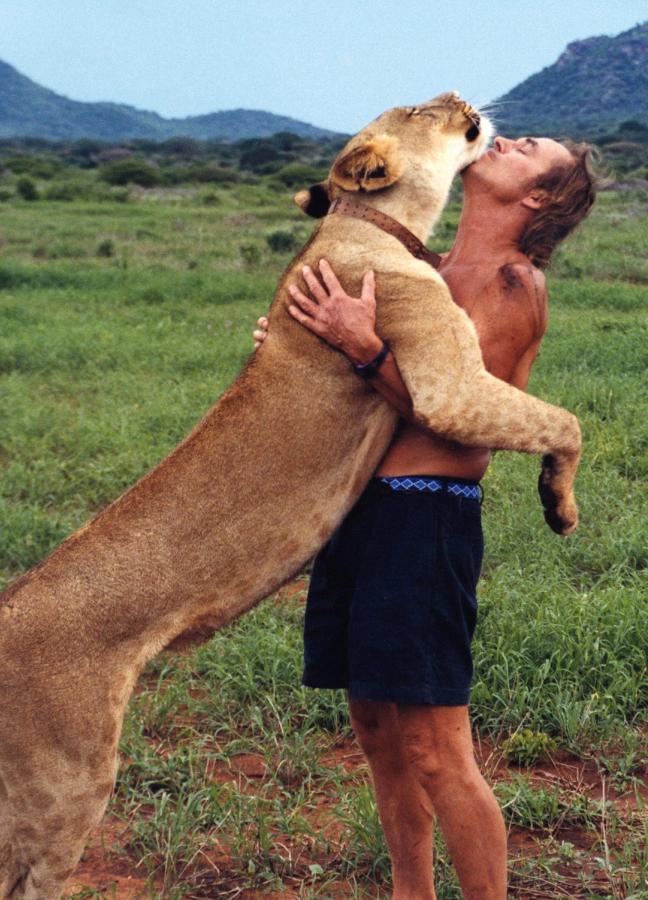

One afternoon, Fitzjohn was returning home to camp from a supply trip when he spotted a small group of lions circling and turning in the dust. One of them had caught a guinea fowl, and Fitzjohn headed in to take it off her — at which point a much larger lion, hiding in the scrub, pounced on him.

“When it actually happened I just thought: shit, I’ve been caught out,” Fitzjohn says. “None of them saw it coming, and in that thick bush you tend to rely on those youngsters as your early warning system, because it’s better than your own.”

The lion trapped Fitzjohn in his jaws by his shoulder and neck, thrashing him on the dry ground. “I kept coming to and blacking out, coming to and blacking out,” he says. A young lion called Fred, who Fitzjohn had saved as a one-month-old cub, jumped at the bigger beast, which had been driven mad, they later learned, by poisoned rhino meat left behind by Somali poachers. “My mate Freddie saved my life,” Fitzjohn said. “He bought time for a guy in camp to alert George, who then came out with a stick and bluffed the lion off me, just as it was dragging me away to eat me.”

Fitzjohn remembers standing bolt upright in a state of bloodied shock and horror. “I put my hand to my neck at the front, and it came out somewhere near the back,” he says. “I asked George: ‘Am I dying?’ He said: ‘I think you probably are, but we’ll take a look at you.’ Lovely people, but tough old boys,” Fitzjohn laughs.

“We didn’t have any painkillers or drugs. George had some veterinary valium, which was all crumbling, but I couldn’t get it down. He gave me a bottle of brandy, but every time I tried to drink it it would flood out of the hole in my throat and pour all over me. So that was no good.”

Terrence came in later and poured a bottle of Savlon over Fitzjohn’s bloody head. “I ended up having about 70 stitches, and they had to sew an ear back on. But I was lying there all that night, waiting to die.” The mauling had happened at about 4.30 pm, but the flying doctors said they couldn’t get to Kora and back before nightfall.

“So I was just lying there. And when the shock was gone, the pain came in. I thought about dying, and as I did, this lovely, warm, petted-in feeling would creep up from my feet, up my legs, and spread all over me. But I realised that if I wanted to stay alive I’d have to fight that, and stay awake — which hurt.”

Somehow, Fitzjohn made it through the night — shaking himself awake every time the warm darkness sucked him under. “The airstrip was an hour and a half away over a rollercoaster road. And I remember sitting there, just before the plane came in, and thinking: ‘fuck, I can’t keep this up.’ Then the plane arrived with morphine, and I was just about okay.” he says.

And then, suddenly: “But it doesn’t weigh heavily on me. Racing drivers have crashes, mountaineers fall off mountains. You’re going to have misfortunes and make mistakes. But so what? I’ve got no right shoulder and he took a big chunk out of the muscle on my neck and ate it. But I live with that. Other muscles grow. You cope.”

"He bluffed the lion off me, just as it was dragging me away to eat me...”

Does he think of himself as lucky? Blessed, even?

“Listen, I think there’s something out there. I’ve got very close to it in nature. All the old boys here that were my mentors, and that I adored, wouldn’t go ‘cheers’ or ‘bottoms up’ when they had a drink — they’d just raise their glass and say: ‘here’s luck.’”, Fitzjohn says. “I wouldn’t put myself in that spiritual capacity. But I don’t think I do this for no reason. I think there’s something unreachable out there that I can’t put my finger on. I got very close to it with the whole man-animal relationship thing, and surviving all those bad times,” he says. “But who’s got the answers?”

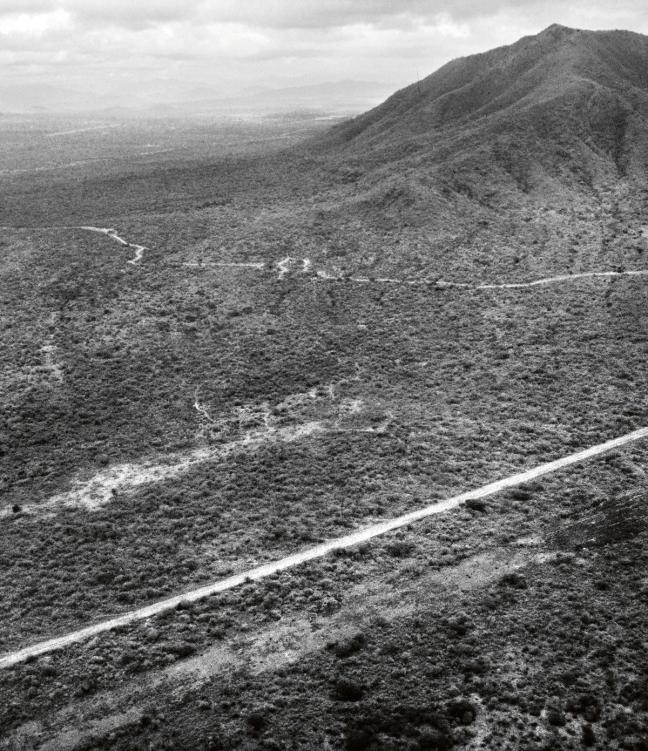

In 1989, Fitzjohn left Kora and headed south across the border. The Tanzanian wildlife division had asked him to take over the Mkomazi National Park — a barren expanse of scorched earth, razed by herdsman, turned to dust by cattle farmers, preyed upon by poachers and bandits. Fitzjohn packed a Land Rover with materials and supplies and ventured into the wilderness. There was nothing there.

“It took me four days alone to get into where I was going to build the camp,” he says. “On the top of the car I had building materials and drums of fuel. I built my tent on the ground, but it soon collapsed. So I lived under the ground sheet for a while.”

Eventually, he began to make headway — constructing a camp, piece by piece, by hand; building the infrastructure from scratch, surveying the landscape, erecting fences, putting down airstrips. “I had to make the roads up myself. And slowly, as the elephants came back, they would follow my own roads, which was interesting.” he says.

“It was an impossible job at the time, but I remembered the odd thing that George used to say: ‘just put one foot in front of the other.’ It’s all common sense — not that they teach that anymore…”

To get the proper lay of the land, Fitzjohn soon learned to fly. “I had pals out there that taught me, which mainly involved having quite a few beers and trying to work out where the ashtrays were,” he laughs. “Navigation was quite tricky. There was no GPS back then, so that was quite fun. But mostly you just make it up yourself. If you don’t fall out of the sky, you’ve kind of worked out how to do it.”

Fitzjohn decided that his focus at Mkomazi would be rhinos, and the rebreeding of African wild dogs. In 1980, there had been over 10,000 rhinos in Tanzania. By 1985, there were just 25.

“We lived through the slaughter of the rhinos and the slaughter of the elephant and the government not doing anything about it,” he says. “By the time I got to Tanzania the rhino had all been wiped out. There were none left. We wanted to do something for them, but it was unattainable — it was so expensive. You need fences, space, and they need peace and quiet. But once I decided to do it, it was extraordinary the support I got.”

One day, a few months into the project, Fitzjohn decided to head back to Kora to collect his old mentor and show him around Mkomazi. Adamson had decided to stay at the Kenyan park when Fitzjohn left for Tanzania, despite growing political tensions and pressure from bandits and poachers. “He was too old to leave. You couldn’t remove George from Kora. He would just wither away and die; he would have been completely lost.”

On the journey over, however, Fitzjohn heard the news. George had been murdered by Somali thieves. “We had kind of been expecting it,” Fitzjohn says after a pause. “He was isolated, I had been forced out — and then they got him.”

The killers had been lurking around the park for a while, apparently. And when a car left the compound, they pounced — breaking both the legs of the cook inside, and raping the European tourist who’d been driving. Adamson rushed in to help them and was shot dead. “In the end, he went out like a charging lion,” Fitzjohn says. “I just thought: fuck it. I wish I had been there. But I wasn’t.”

“I realised after that that I had to make a success of Mkomazi. I was doing it in George’s name,” Fitzjohn says. “I never thought I had the patience or capacity for it. But at the back of my mind I knew that I didn’t want to let George down. Because I wasn’t there when he was murdered. Had I been there, it probably would never have happened.” He pauses. “I got quite sad three or four years after his death, and beat myself up a bit for not being there. But I knew I had to stay true to what he and I believed in.”

After Adamson’s death, Fitzjohn began to realise he had a problem with alcohol. The task in front of him at Mkomazi was improbable, to say the least — but it would be downright impossible in a constant drunken, hungover haze. Soon, friends had checked him into a rehab clinic in Hazelden, Minnesota.

“It was the best thing I ever did. I could never have achieved what I did without that change of perspective on life,” he says. “And you know what? What a relief that was. Learning to behave again took a lot of time — but then my wife Lucy came into my life, and I had a chance to become whole again after all.”

Mkomazi has been a resounding success — one of the great triumphs of modern conservation, against overwhelming odds and amid a tumultuous political landscape. Over three decades, the sanctuary and breeding programs have far exceeded all expectations. Today, there is a breeding population of more than 33 rhinos, and over 200 wild dogs have been released into the wild.

His efforts have been endorsed and supported on both a local and international scale, by a web of organisations (like Tusk, US Fish and Wildlife, the Leonardo DiCaprio Foundation, and the George Adamson Wildlife Preservation Trust, which was set up in 1988) and a nexus of wealthy individuals and influential friends.

Fitzjohn raised a family on the park with his wife, Lucy: three girls and a boy, who grew up among the animals half the year, and boarded in England the rest of the time. He was awarded an OBE in 2006. The elephants flourished, the documentary crews visited, the air strips were lengthened, the work rumbled on.

In 2019, however, Fitzjohn began to sense a change in the air. The Tanzanian government, who had steadily been earning more and more money from commercial conservation, tourism and safaris, saw Mkomazi as a fatted calf.

“Their eyes were all glittery. I saw them moving in. They said: ‘it’s not secure enough,’” Fitzjohn explains. “I’ve always been light on guns, heavy on comms. I believe in presence and activity, not loads of armed guys standing around doing nothing — that’s the way I do things.”

"Learning to behave again took a lot of time..."

In 2015, John Magafuli was elected President of Tanzania. “The first year he was there, he started empowering everyone to be as nasty as he liked,” Fitzjohn says. “They liked the look of Mkomazi, because it looked so glittery. They started investigating me, and it just got nastier and nastier. So I just said: let’s have a proper handover. If you’re going to take all my stuff anyway, let’s make it proper and legal in the eyes of the world.”

Fitzjohn handed the park over to the government in January 2020, and left quietly. “And then Covid hit, and I couldn’t get back there, and I lost most of my things. I just took one car and one tractor,” he says. “But it’s only fucking metal. And I’m young enough to start again — well, young-ish.”

But Fitzjohn does not bear a grudge, and stresses how grateful he has been for the help he received in Tanzania, and the opportunity to do it all in the first place. (“How lucky am I!”, he says at one point.) The feeling seems mutual. “In fact, I’ve already had people asking me, via third parties, if I’d ever consider coming back to Mkomazi. But the answer is no. I don’t go back. I’m going to end up where I belong

Which is why we’re speaking today. Earlier this year, Fitzjohn returned to Kora, the park where it all began, half a century ago. There is a sense of pleasing circularity to this latest chapter; of unfinished business being settled at last. Along with Alexander, his son — known everywhere as Mukka — Fitzjohn has set about restoring Kora to its former glory. Mukka, he says, will probably end up being even better at the job than his old man. “He turned to me recently and said: ‘what did you expect me to be, Dad? A geography teacher?” Fitzjohn laughs. “So we’re off to work.”

“I have GPSed all the existing tracks, and surveyed a lot of the area by air and by land. I’ve just bought a new JCB, and I’m going to go in and start again on all the roads and airstrips,” he says. “Once the infrastructure’s up and running, I’m open for business, as the American say.”

What’s the plan? “I don’t really want to do lions again,” Fitzjohn tells me. “But I really would like to put a rhino facility there. I think it needs an iconic species. I’ll probably start a cheetah program. I may do leopards there. Let’s just see what happens, and see what comes along. It could lead anywhere, couldn’t it?”

George Adamson is buried at Kora, in a simple mound of stones, next to his brother Terrence and one of his beloved lions, Boy. In his 1988 autobiography, Adamson included a famous lament. “Who will now care for the animals, for they cannot look after themselves?” it reads. “Are there young men and women who are willing to take on this charge? Who will raise their voices, when mine is carried away on the wind, to plead their case” In the thirty years since, Fitzjohn, more than anyone, has kept that chorus alive.

“It went deeper than pals, with George and me,” he says. “George was the father figure I was looking for, and I was the son he never had. There was an unspoken bond, which we both would have denied at the time. But you don’t live with someone for that long without there being something deeper,” he says, exhaling heavily.

“So here I am, with another national park tucked under my belt, going back to where I started to try and finish off the job.” Fitzjohn remembers a quote from TS Eliot, told to him recently by an old friend. “It’s from his East Coker poem,” he says: “‘In my beginning is my end.’

“You can take that how you want. But everything that I am today, I owe to Kora. I’m going back to finish off the job that we started — the job that was never finished because I left and because of his murder. It feels circular. It feels total. It’s almost seamless,” he says. “Coming back, it was like never going away. This is where I really need to be.”

This article was taken from the Summer 2021 issue of Gentleman’s Journal. To learn more, and subscribe today, click here…

Become a Gentleman’s Journal Member?

Like the Gentleman’s Journal? Why not join the Clubhouse, a special kind of private club where members receive offers and experiences from hand-picked, premium brands. You will also receive invites to exclusive events, the quarterly print magazine delivered directly to your door and your own membership card.