The Michelin star is dead (long live the Michelin star)

In the summer of 1900, two French tyre makers had an idea that would change the way the world saw food forever...

Édouard and André Michelin knew that if anything could persuade a Frenchman to buy more tyres, it was his stomach, and so the pair wrote a restaurant guide. It was a marketing ploy that proved prescient and genius. Soon, France’s car-owning leisurati were wearing their tyres thin driving from brasserie to gastro-palace up and down France.

By the 1950s, the “tourist’s bible”, as Time Magazine would anoint it, was in every traveller’s glove box in France. Today, the “red book” publishes 28 editions in more than 25 countries. “It is the easiest, the most memorable shorthand term for a good restaurant,” notes veteran food critic and restaurant consultant Nick Lander.

In today’s digital age, however, a growing number of chefs and critics are beginning to question the relevance and integrity of the modern handbook. Is the Michelin Guide finally going off the boil? Or does it have the same authority it has enjoyed for more than a century?

The darker side to success...

“It’s almost like a lifestyle for a chef when you are working at that level,” says Helena Puolakka, former head chef of two three-Michelin-starred kitchens — Pierre Koffmann’s now-closed La Tante Claire in London and Pierre Gagnaire’s eponymous restaurant at Hotel Balzac in Paris. She is now Executive Chef at Aster Restaurant and Cafe in London’s Victoria. “The respect you gain as a chef with a Michelin star, it’s a completely different story,” she adds. “You want to be a part of it because [Michelin] is the bible.”

“I started crying when I lost my stars, it’s like losing a girlfriend...”

Little wonder, then, that when a chef loses a star, it cuts deep. “I started crying when I lost my stars,” said Gordon Ramsey in 2014. “It’s like losing a girlfriend.” Others have fretted to the point of breakdown and suicide about how to stay in the Good Book’s good books. In 2003, French chef Bernard Loiseau — one of the most famous chefs in France and the inspiration for the chef Auguste Gusteau in the Pixar film Ratatouille — shot himself in the mouth amid rumours Michelin was about to pull his restaurant La Côte d’Or’s third star.

Bernard Loiseau, photographed by Maurice Rougemont

A cloud is creeping over Michelin. Most telling, perhaps, are the closures. In the past 20 years, at least eight big-name chefs have shut their kitchens, or asked for their stars to be reneged, to escape what they see as the “curse” of Michelin. Take Sebastian Bras — one of France’s most celebrated chefs — who last September asked to be stripped of the three stars his Le Suquet restaurant in Laguiole had held for two decades, saying he no longer wanted the “huge pressure.”

And most famously, in 1999, Marco Pierre White walked out of the Hyde Park Hotel in Knightsbridge, effectively giving up the three stars he’d been the youngest on earth to earn.

A call for change...

Simpler food. That’s what real Londoners hunger for, according to many of Michelin’s critics. Or, as the late A. A. Gill put it in 2015: “In both London and New York, the guide appears to be wholly out of touch with the way people actually eat, still being most comfortable rewarding fat, conservative, fussy rooms that use expensive ingredients with ingratiating pomp to serve glossy plutocrats and their speechless rental dates.”

"The guide appears to be wholly out of touch with the way people actually eat..."

If you think three-Michelin-starred food is expensive, it’s nothing compared to the Michelin Guide’s overheads. It won’t reveal its inspectors’ salaries, nor even how many there are — their identities are as closely-guarded as state secrets. (This, it says, plus the fact they always pay for their food, is how they stay impartial). But it doesn’t take a quant to imagine their expense forms. And given how many more restaurants there are in London alone compared to three decades ago, it goes without saying that Michelin’s guide is a very expensive operation.

Given all the controversy, does the Michelin Guide still have the same currency in London it has enjoyed in Europe for more than 100 years? Or is it going a little deaf with age? Are younger, trendier guides stealing its limelight — like the World’s 50 Best Restaurants, the National Restaurant Awards (only two of its Top Five this year were Michelin-starred), TripAdvisor, Open Table, even Instagram?

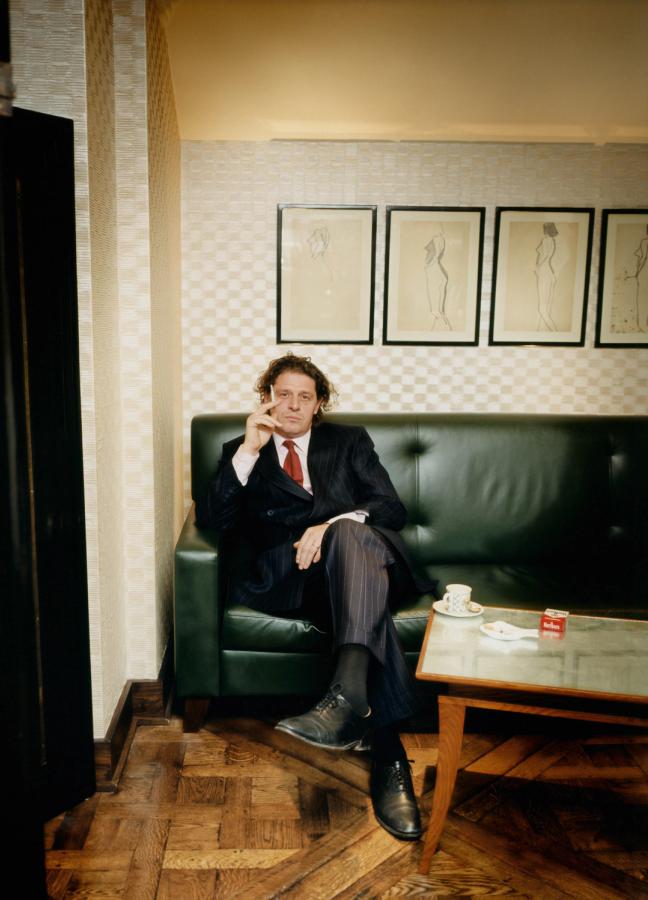

British celebrity chef Marco Pierre White, circa 1988. Photo by John Stoddart.

What the future holds...

“Here’s the thing,” one head chef who asked not to be named, but has worked at the top-end of the industry for ten years, tells me. “Chefs used to crave the love and attention of Michelin, like the child of a stern parent. But now that child has grown up. He has other outlets. He no longer needs the validation.”

What does the future hold for the world’s most famous guide? “I certainly don’t think it is dead,” says Lander. “They’ve cleverly tapped into the Chinese and Japanese markets, and as long as England remains incredibly good value for these people, and tourism grows, they will plan their journey around Michelin-starred restaurants. And that will be good for them, for Michelin and for the restaurants. But I do think it’s lost its lustre.”

“I don’t like going to a restaurant and being made to feel like I’m going to pray at their alter..."

“I wouldn’t like Michelin to lose it’s currency,” adds Puolakka. “I think it’s important. It has that history. There’s nothing wrong with the classics, or with doing things the old-fashioned way. Yes, there are other ranking systems, which is really exciting. And yes, there are tenfold more great restaurants in London than you would read about in the Michelin guide. But it is still the bible.”

As for Lee and Kate Tiernan, the customer is their god. “I don’t like going to a restaurant and being made to feel like I’m going to pray at their alter, which you get in many of the more old-school Michelin-starred restaurants,” says Kate. “‘You’re very lucky to be here’, is the message. But I’m like, ‘I’m dropping £500, I don’t feel that lucky.’”

Then she laughs: “At the end of the day, it’s just dinner. And if I’ve learned one thing in 21 years in the restaurant business, it’s about about having a good time. You can’t digest your food if you’re not having fun.”

Prefer to eat at home? Here’s how to make Marcus Wareing’s perfect beef pie…

Join the Gentleman’s Journal Clubhouse here.

Become a Gentleman’s Journal Member?

Like the Gentleman’s Journal? Why not join the Clubhouse, a special kind of private club where members receive offers and experiences from hand-picked, premium brands. You will also receive invites to exclusive events, the quarterly print magazine delivered directly to your door and your own membership card.