The first time Rudy Tarditi won big, he was just eight years old. On a family trip to the Casino de Monte-Carlo, his father stopped him just short of the grand front doors, and presented him with a single franc. He gave young Rudy a choice. Either keep the coin, or task his father with venturing inside, finding a slot machine and playing it. Rudy went for the gamble, waiting patiently on the square until, eventually, his father reappeared — holding two francs.

Decades later, Rudy remains at the casino. Today, however, he is its general director. Buttoned into a trimly tailored suit, he’s recounting the win on his office balcony, under a mighty Monacan sun.

“That was my first experience with the casino,” Tarditi tells me. “And two francs? It was important. Incroyable! But, my father told me then I should never play again. So, I haven’t. I’ve never played here since”.

He couldn’t even if he wanted to. Gambling is contractually forbidden for every employee of the Monte-Carlo Société des Bains de Mer (the organisation that owns and manages the majority of hotels, restaurants and beach clubs in Monaco). It’s also illegal for any Monégasque, a citizenship Tarditi now holds, to place a bet inside the Casino de Monte-Carlo.

“It’s for our own protection,” he shrugs, explaining that when the casino opened, in 1863, the sovereign who masterminded its construction, Prince Charles III — for whom ‘Monte-Carlo’, literally ‘Mount Charles’, is named — decreed that his citizens would never be allowed to play. The project was to bring prosperity; not misfortune.

“Monaco’s first trick was to legalise gambling,” says Tarditi. “Until then, there was no tourism here — as Monaco was only accessible by boat. But, Prince Charles III was clever enough to create that magic, and build a new city in the city. A place where everything is possible”.

But, Charles had help, adds the casino director. French businessman François Blanc, who had established an eminent casino in Frankfurt, the ‘Spielbank Bad Homburg’, was coaxed to Monaco and tasked with conjuring up similar noise on these shores. He would later earn the nickname ‘The Magician of Monte-Carlo’, after successfully tempting travellers here from nearby Nice.

That explains the clock. Step off Tarditi’s balcony, back inside the casino and you’ll find it hanging from the ceiling of a palatial ‘salles de jeux’. Golden and glorious, it is the most prominent casino clock in the world (casinos, in fact, rarely contain clocks at all). But, this was a necessary flourish, installed so gamblers past could keep time and, in the absence of roads or railways, catch the last daily boat out of Monaco.

Such boats still ferry visitors along the Riviera today. You can spot them, bobbing in sparkling waters, through the casino’s expansive windows (another rarity; most casinos lack windows of any sort). But, with views like these, how could the Casino de Monte-Carlo close itself off from the world? Instead, the establishment has embraced its salt-sprayed scenery, building vast open-air terraces that teem with waterproofed gaming tables.

These departures, Tarditi continues, retreating inside, are only the first of the casino’s many luxurious lures. From a majestic marble-columned entrance hall to those sea view terraces, the establishment stretches across countless cavernous gaming rooms, each awash with gilded paint and fitted with plush, patterned carpets. As opulent as it is elegant, this décor is the second customer draw Tarditi counts off on his fingers.

“They come for the history. For the style. For the legends. For the great art of gaming. And, of course, for James Bond…”

Downstairs, in the ‘Salle Blanche’, Giuseppe Cavaliere is suavely mixing drinks behind a great, glittering bar. This space was once a renowned literary salon and Cavaliere, like Tarditi, is invoking Bond’s influence. Much of his day, says the barman, is spent serving up dry vodka martinis.

“Shaken, not stirred,” he smirks. “Many, many people request this cocktail — because Pierce Brosnan drank one here, in GoldenEye”.

Martinis are just one of the epicurean pleasures to be found in the Casino de Monte-Carlo. Cavaliere works two bars and, in the ‘Salon Rose’ restaurant — where a yolky beef tartare upholds tradition, and both bream and bass are fished from the sea outside — the oil-painted ceiling is stained brown with cigar smoke. From the cornicing down, it’s a pristine dining room. But, the mural overhead was left untouched during restorations, hidden behind this tinge of tobacco, and serving as a salient, sentimental reminder of the casino’s more bacchanalian days.

“They come for the history. For the legends. For the great art of gaming…”

But, back to 007. Because more Bonds than Brosnan have had a flutter in Monte-Carlo’s hallowed halls. Sean Connery’s spin on the spy visited in Never Say Never Again, and, although it wasn’t filmed in Monaco, the first ever iteration of the secret agent (played by Barry Nelson in a 1954 episode of Climax!, adapted by Ian Fleming himself) was set at the casino. Much to Cavaliere’s chagrin, Nelson’s Bond ordered a simple scotch and water.

Because the barman gets a thrill from martini-mixing, he, like almost all of the staff, relishes the casino’s connection to Bond. And, when he moved here from San Remo five years ago, he did so for this “prestige”.

“We only close once every table in the casino is closed,” Cavaliere adds. “When the gambling finishes, we finish”. Officially, that’s 4am most nights — although the casino pushes this to 6am, when the wealthiest high-rollers request it. The barman floats away, tray braced on outstretched fingers. The piped music changes; a classic crooner in Italian giving way to trumpet-heavy jazz. It’s a John Barry score, brassy and shriller than the supercar tyres squealing on the square outside.

That square is the gateway to the casino. Two years ago, it was entirely remodelled and, though Anish Kapoor’s 1999 ‘Sky Mirror’ remains, the rest of the palm-lined plaza was pedestrianised, paved with this oddly squealy stone. Visit today, and the only cars you’ll see parked on the Place du Casino are the eight motors manoeuvred into prime positions outside its doors. This is the work of the ‘voituriers’, the casino’s fleet of impeccably dressed parking valets.

“And these spaces,” says sun-tanned valet Mikael Verrando, “are for our very good clients. These clients will always have such privileges — even if they come in a Smart car”.

Verrando, resplendently cool in his crisp, off-white uniform, began work at the casino nine years ago. He started as a doorman, before becoming a private chauffeur for VIPs. For the last five years, he has been a ‘voiturier’ — and he is happy.

“Driving all of these beautiful cars?” he nods at an approaching Aston Martin. “How could I not be happy? I think I was recruited because I am a calm driver; never stressed. Although, most modern cars have electronics — tools that help you drive them. It’s much more difficult with the older cars”.

But, even the oldest cars don’t daunt Verrando. He may have to stifle his excitement when a Ferrari Pista, his favourite supercar, pulls onto the square, but, as a born-and-bred Monégasque, the valet has spent a lifetime surrounded by incredible vehicles.

The annual Monaco Grand Prix is, unsurprisingly, eagerly awaited by every ‘voiturier’. During the race weekend, the Place du Casino square is closed, so the valets collect cars from the nearby Hôtel Hermitage. Casino guests are then shown into the Hôtel de Paris Monte-Carlo, ushered into a hidden lift and guided under the square through a secret subterranean tunnel. When Winston Churchill would visit the hotel, he’d use the same passageway, emerging beside the gaming tables (where Aristotle Onassis would allegedly bankroll him chips).

And, yet, while the Formula One fixture may keep some traditions alive, the square is never short of high-calibre cars. “Here,” says Verrando, “we see the world’s most expensive cars all year round. Ferrari Monzas. Bugatti Chirons. Porsches. Bentleys. Lamborghinis”.

And, each is praised and protected in equal measure. A valet stands guard over the key box at all times. There are police and cameras everywhere, says Verrando. There’s even a prison here — albeit one with a sea view.

But, security needs to be tight. Across the casino’s sixteen high-rolling centuries, many men have attempted to ‘break the bank’, often through means nefarious. In 1891, fraudster Charles Wells won big — earning himself notoriety, much suspicion and the equivalent of €13m. Today, money changes hands at suitably chic cash desks, dotted about the gaming floors and crowned with the word ‘Caisse’ in Art Deco type. Particularly well-heeled guests also have a team of hosts at their disposal, to muster up almost anything they desire.

“Whether that’s a Diet Coke, or a helicopter”, says Thomas Bonafede, with a smile. As the VIP team’s congenial leader, Bonafede has fielded requests from the fantastic to the farcical. “It can be anything — within the law”.

Perched in the casino’s ‘Salle Schmit’, and greeting every passing visitor, Bonafede is explaining how a recent demand required him to lobby for a law change. A “huge” VIP had refused to visit unless he could walk his dogs in a nearby public garden – so, the casino was forced to ask the government to lift certain restrictions. They did. Another request saw the host close the on-site opera house [designed by Charles Garnier, it is a quarter-size recreation of the ‘Palais Garnier’ in Paris] to facilitate a guest’s lavish proposal to his girlfriend. “Thank God she said yes”, Bonafede laughs.

Before hosting high-rollers, Bonafede began at the casino as a croupier. Today, his team of 12 speak 14 languages, and, while the VIPs were once predominantly Russian and Chinese, they are now Middle Eastern. Yet, one constant, he says, connects every nationality.

“These bizarre requests. And, while they sounded crazy to me at first, they’re now routine. I also believe that a lot of the top gamblers don’t come for the games themselves. Instead, I believe they come to play with us. To play with the hosts, test our limits and push us that little bit further. To see what they can get. I call that the ‘meta-game’”.

And, whether it be plum parking spots or signature serves at the bar, exclusivity appears to be the name of this particular game. Even the grand gaming floors aren’t select enough for some guests, says Bonafede. Upon following the host through a warren of secret corridors and private gaming suites, it becomes clear that there is more casino within the casino than any average punter will ever see. In one hidden room, a full-size roulette table sits under a large landscape artwork. “Every painting,” says the host, “even the ugly ones, are really quite valuable”.

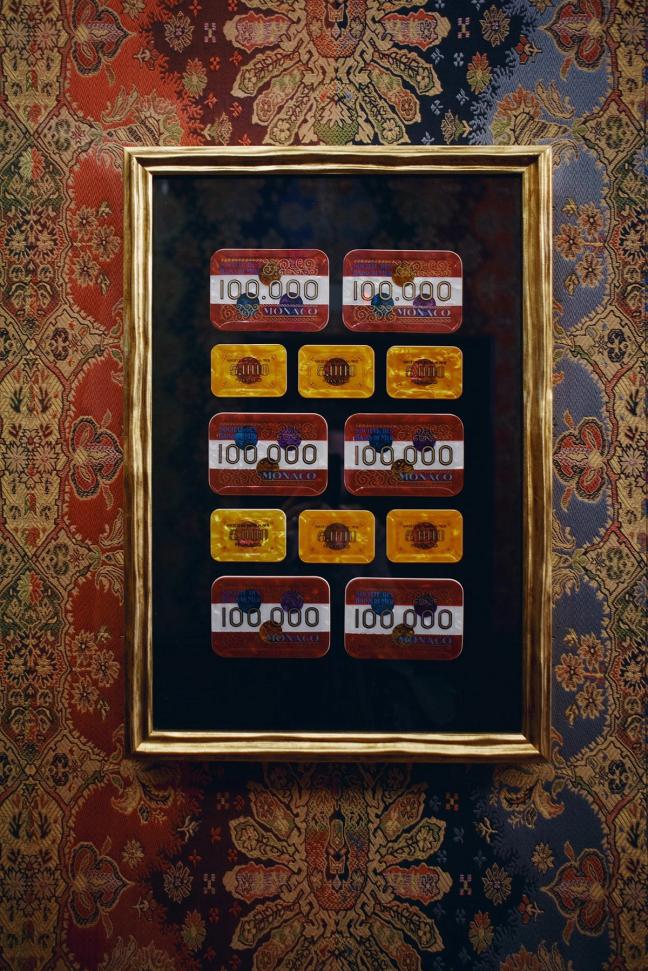

There are also gaming plaques and tokens, framed and hung on ornate silk wallpaper. When the Casino de Monte-Carlo opened, Bonafede says, it used chips of pure gold. These were replaced with fishbone chips and, in turn, plastic, which bear an exclusive design that changes every 20 years. The playing cards, however, are standard. A dedicated team deals with these decks, and, in games such as Baccarat, where the cards are bent, the entire pack is thrown away after every round.

“They first rebuild the deck,” explains Bonafede, pushing open a door concealed in the wall. “Then, once re-ordered, they pierce it all the way through using a special machine, and send it away to be destroyed”.

But, the casino’s most famous game doesn’t require cards. French roulette, which a junior croupier tells me is “the game upon which the casino turns”, is the quick-spinning reason many visitors take their trips to Monte-Carlo. The numbers on the wheel are ordered differently from the American game, and there is only a single green zero. It also requires three dealers and a table manager — or ‘Master of Ceremonies’ — to play, meaning croupiers often outnumber players.

“It’s called ‘French’,” smiles Bonafede, “because it makes no sense”.

“Every painting, even the ugly ones, are really quite valuable…”

That may be so, but the Casino de Monte-Carlo still maintains more French roulette tables than any other establishment worldwide. Bonafede also calls it a “dying game”, revealing that, while there are a handful of tables in Germany and Belgium (curiously, none in France, itself), this is the only place you’ll find more than one. It’s a hard game to master, and, in the nine years it takes a Casino de Monte-Carlo croupier to learn their craft, the final six months are dedicated solely to its many quirks and conventions.

Back in the farthest-flung gaming room (a huge space where boxing championships are sometimes held) croupier Mikaël Palmaro is doing his best to explain to me the intricacies of French roulette. He has a delightful roulette wheel wristwatch, an even more delightful way of pronouncing ‘caz-eeno’, and sixteen years of experience since enrolling in the casino’s ‘School of Gaming’ in 2007.

“This job is quite often passed down,” he says, brandishing a roulette rake. “My great-grandfather was a French roulette croupier at this casino, and, my father, who was a croupier on card games, Chemin de Fer in particular, was games manager here for 17 years”.

Whether shuffling runs in your blood, or you’ve never rolled a die in your life, every prospective croupier is required to train in-house. Behind Palmaro, trainees are clustered around a handful of tables, each of them impeccably dressed and diligently listening to their instructor. This class is many months into training – but, the initial selection process is arduous.

It begins with dexterity tests; drawing perfect circles to gauge hand-eye coordination. If you’re discovered to be colourblind, you will be eliminated. If you fail the battery of computer-based calculation exams, you will be eliminated. And, if you make it that far, you must pass three days of intense psychological role-play, set and supervised by a qualified therapist.

“Of course,” Palmaro adds, rake still in hand, “even if you are the best croupier, you still need the right tools. We can’t offer the client a good experience without this. But, I think our roulette wheels are possibly the most beautiful in the world. We’re really spoilt, purely because everything is made in house, with savoir-faire passed down through generations”.

‘Savoir-faire’. It’s a phrase that echoes around the casino’s vaulted ceilings; a watchword for every employee, from Rudy Tarditi to Maxime Julien, an electrician tasked with fixing any faulty equipment. Julien’s chief responsibility is minding the slot machines, which pay out around €117,000,000 every year.

And, though the flashing lights and neon screens may, at first, look out of place here, the casino has long led the electrical charge. In the 19th century, Belgian inventor Zénobe Gramme staged high-voltage experiments in the building’s basement. Before Tesla made his first breakthrough, Gramme had set out to make Monte-Carlo the world’s first town with electric lighting. It’s a dynamic legacy that lives on today: as Julien explains, the casino is the first to connect a French roulette table to a digital ‘Spintec’ machine.

“What makes that special,” says the ‘electromecanicien’, “is that we can, essentially, make the table bigger, and give more people the chance to play this rarer roulette. Because, while the tables are built using incredible savoir-faire – even the noise of the wheel is engineered, so the ball makes a pleasant sound – they can be daunting. By using ‘Spintec’ screens to join the game, people are eased in, and encouraged to transition, eventually, to a live table”.

And, it's at these ‘live’ tables, though manually staffed and played, where the electricity really crackles. Jérôme Tachoires is the technical gaming manager for the Monte-Carlo Société des Bains de Mer, and runs the in-house workshop where casino kit is fabricated. He’s been here for 30 years, but can often still be found on the floor, checking the condition of the roulette wheels, the fine furniture – even the small, polished placards that signpost playing requirements and minimum bets of the tables.

Today, Tachoires is overseeing the cleaning of a French roulette table. Every day, they are checked, vacuumed with handheld Dyson cleaners and polished from their top rails to their wheel turrets. They are clad in a wool softer than baize, woven by the same Belgian brand that supplies the King’s Guard, and dyed ‘Monte-Carlo Green’, a shade exclusive to the casino. Once unfurled in the workshop, this fabric is stapled to the custom-built tables and methodically spot-dyed with nitric acid to create the distinctive yellow markings of a particular game.

“This is a know-how that can’t be found anywhere else,” Tachoires nods, running his hand around the bowl of a roulette wheel. “Every table is polished a minimum of 30 times before it enters the casino. These wheels are crafted with different woods: ebony for black numbers, rosewood for lighter numbers and beech for the divides. There are no tables numbered 13, for obvious reasons – and, no fourth position at the Punto Banco tables, as that’s an unlucky number in China”.

Tachoires’s team of eight is split into five departments: carpentry; upholstery; mechanics; printing; and checking. And, ever since the workshop was established, in 1863, the same year as the casino, the manager maintains that every piece it’s produced has been “perfect”.

“We have to be perfect,” says Tachoires. “If a client asks a question about why something is a certain way, we must have the answer – and can prove we have done nothing wrong. We owe this clarity to the clients – but, also to our employees, so they can work with clear minds”.

The clearest of the casino’s minds might belong to Stéphane Hvala, the institution’s buoyant Croatian doorman. All smiles, he has been welcoming guests and holding doors for almost three decades. Standing on the stairs outside the casino, he’s explaining that his surname translates to 'thank you'. It’s funny, we say, as that’s likely the phrase he’s heard most in his life.

“Everything has changed since I started!” he beams from under his brimmed cap. “Except for the ways of the customers. When they return – mad, happy or angry – I must still smile and tell them that tomorrow is a new day. I am the first – and last – person they see, so I must always be happy. I am their psychotherapist, trying to find that exact little word or phrase that will end their night in a good way”.

Come rain, shine or 38-degree heat, you will find Hvala standing on the square. He’s welcomed Nelson Mandela, Bill Gates and Bono to Monaco. George Bush once said hello at 2am, when the Place du Casino was empty and very, very cold (during winter, he is given a small fur cape to keep warm). He stars, albeit briefly, in Ocean’s Twelve. “I’m the one opening the door,” he says, deadpan. And, although Roger Moore’s 007 never set foot in the storied casino, the actor did live nearby until his death, in 2017, and was a regular presence on the square.

“He always had a good word for everybody,” says Hvala, with the same cheer and zest he uses when talking about most people – patrons or not. Because, like Giuseppe Cavaliere shaking martinis behind the bar or Mikaël Palmaro taking bets at the gaming tables, Hvala is at his happiest when working hard and playing his own precise part in the Monte-Carlo machine. And, as that mighty sun dips down, it’s easy to see why Hvala considers his the best hand dealt.

“It represents Monaco,” says the doorman, hands outstretched as if warming himself on the square’s golden glow. “It’s wonderful. The most beautiful place in the world. And that we all get to work for this unique casino and spend every day here? That is very special. I am 55 now, but I will stay here forever”.

This article is taken from the 10th-anniversary issue of Gentleman’s Journal. Have a flick through our other features here…

Become a Gentleman’s Journal Member?

Like the Gentleman’s Journal? Why not join the Clubhouse, a special kind of private club where members receive offers and experiences from hand-picked, premium brands. You will also receive invites to exclusive events, the quarterly print magazine delivered directly to your door and your own membership card.