Oceanography, philosophy, mortality and toffs: Theo James goes in at the deep end

“The Gentlemen is fun and bombastic,” says the actor of his leading role in Guy Ritchie’s new series. “But the heart of it – the idea of indentured wealth, class and money handed down over generations – is very interesting indeed…”

In Sicily they have the mafia, in Sinola they have the cartels, but in Shropshire they have something truly sinister: the aristocracy. (Other home counties are available, of course.) That’s the bubbling premise, at least, of Guy Ritchie’s latest show, The Gentlemen, which sees Theo James star as a thirty-something posho who inherits the creaking family pile – only to discover that he’s unwittingly become something of a drugs kingpin in the process. Holes in the roof and hydroponics in the wine cellar.

The series is Ritchie at his tweed-and-weed best, stitching the underworld of his nineties pomp into the silkier charms of his Oxfordshire lifestyle. In the first 60 seconds of the trailer, alone, there are clay pigeons and cocaine, choppers and Cotswold stone, car chases and Cohibas, black-tie parties and nasty pieces of work – there's even Ray Winstone in some exquisite tinted shades. All great fun and just what the doctor ordered. I could watch Vinnie Jones in a Barbour for hours. But, as soon as you get talking to Theo James on the subject, you begin to realise that that central conceit runs much deeper than the puns and pyrotechnics.

“I’ve always been fascinated with the British class system and how it informs every asset of our unconscious social-economic structure,” James says, as we chat over the phone on a recent afternoon in February. “Yes, The Gentlemen is fun and bombastic, but the heart of it – the idea of indentured wealth, class and money handed down over generations, is an interesting feature.” In one moment, early on in The Gentlemen, an American character describes how “the aristocracy are the original gangsters”. James says the line goes on to explain that “what they did is control the judiciary, control the land ownership, control every aspect of our society – and, then, set up a system where they can hand it down to their families for the rest of time.” The gentry’s 'people like us' is just the mafia’s cosa nostra – this thing of ours – with added gout. And, anyone who’s ever said ‘toilet’ when they meant ‘loo’ will know the codes are just as binding and brutal.

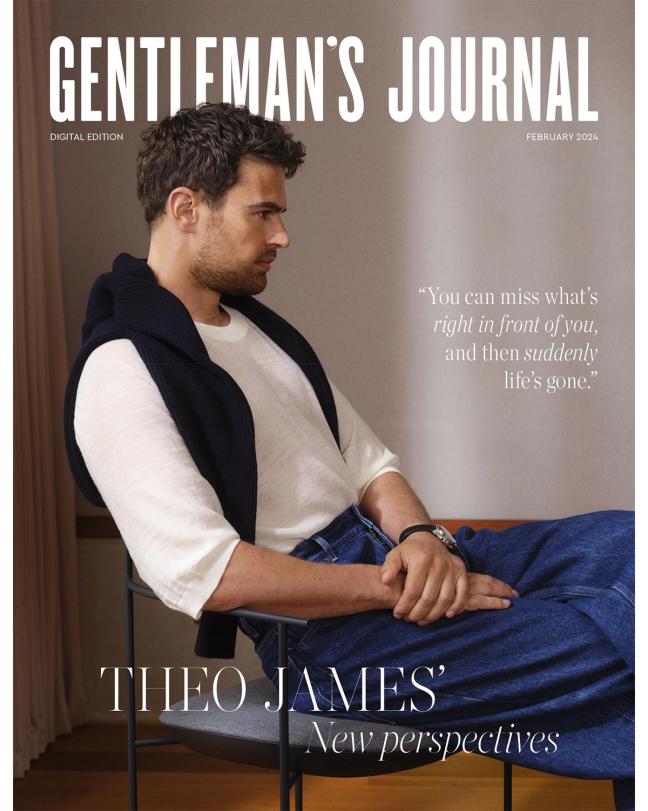

Overshirt by Canali, canali.com; T-shirt by Slowear, slowear.com; Trousers by Daniel W Fletcher, danielwfletcher.com; Socks by Falke, falke.com; Shoes by Tod's, tods.com

So, we’ve jumped right in at the deep end. But, I suspect that’s where James likes to be, both literally and figuratively. When he was growing up – the youngest of five children on an old farm near Aylesbury, in Buckinghamshire – James wanted to be one of two things: either an oceanographer or a philosopher. In the end, acting won out, after an on-again-off-again flirtation with rock and roll. There is a sense of the inevitable, here, of the pre-ordained – especially when you watch James in something like The White Lotus, in which he brilliantly renders his Cameron as the sort of voracious, devastating, domineering finance bro we all hate to love and secretly hope to impress. He has the face of a leading man and the nuance of a character actor.

Besides, James says, he didn’t have the disposition for academia. But, as we talk, I can almost imagine him in an alternate reality as some tweedy young lecturer, strolling with a leather satchel across a cobbled campus, batting off yapping undergraduates who want to name-drop Wittgenstein and ask him where he gets his cords.

Our conversation was, in many ways, the normal, friendly actor-journalist fare (at one point, squinting at my questions and losing my flow, I asked the unforgivable: “and have you always been a fan of Guy Ritchie’s work?”). But throughout, James gently indulged me with little glimpses of the good stuff, the Kierkegaard stuff, the real 3am stuff.

So, King Herod, who James played in his first nativity outing, becomes filled with a “strange humanity”. A handsome country house leads us on to the legacy of the Empire. And the question of writing a book takes us into the seductions of immortality. I think he would have made a great oceanographer.

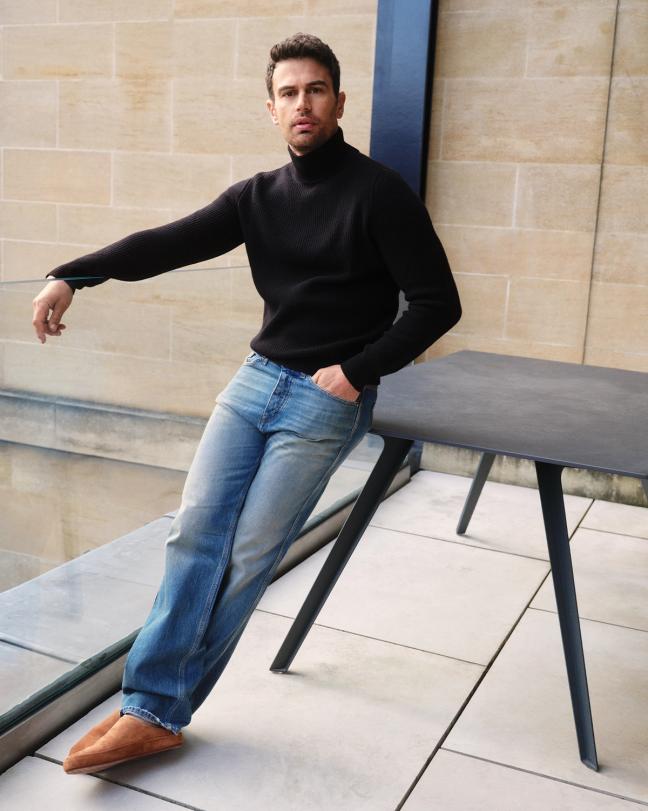

Jumper by Luca Faloni, lucafaloni.com; T-shirt by Zegna, zegna.com; Jeans by Studio Nicholson, studionicholson.com.

JB: You’re the youngest of five children. I happen to be the youngest of six. As I get older, I realise how much my position in the family might have shaped who I am. Do you think that’s true of you, too?

TJ: You like to tell yourself that family, and certainly your position in it, have no currency in terms of the person you became. But I agree: being the youngest definitely afforded me luxuries my other siblings didn’t have. You have less scrutiny on you as the youngest child; you have a little more freedom. I think for the eldest as well, the weight of expectation, anxiety, nerves from parents… just thinking of myself, I have two children, and, having the second one, you’re much more relaxed and laconic, existentially, as a parent.

And I think it’s not an accident that I’m an actor, or trying to perform in some way. We had a very busy household, and you know what it’s like – there’s always girlfriends or people in the house, so there’s always 10 people there at one time, and trying to find a space in that lends itself to trying to be loud or perform and get attention in some ways, which I think lends itself to what I ended up doing as well.

“I think people get addicted to the elixir – fame, TV shows, magazines – and find it hard to leave that behind”

Was acting always the thing, then?

I didn’t always know. I was always interested in the ocean and the sea. I was going to do oceanography as my degree, but, then, as I grew older, my interest in biology waned, and I didn’t take it as an A-level – that sort of knocked itself on the head, and I ended up doing philosophy. I liked, and I still like, philosophy, and flirted with the idea of academia, but, again, reality quickly told me that that wasn’t going to happen. But I enjoyed it very much.

I certainly liked performance. I liked being on a stage, even though it made me nervous. I kind of enjoyed that, and I remember understanding that feeling quite early. I was King Herod – it’s still a vivid memory. I remember being on stage and trying to tell a story and capture people’s attention in whatever way.

Herod! That’s a complex first character.

A very complex character! Terrible person. But one filled, in strange ways, with humanity. But, then again, I was seven, so there wasn’t too much humanity. Just glaring looks and shouting. I had a scary fake beard, I think, and a whip, I seem to remember.

Trench coat and top by Hermès, hermes.com

Trench coat, top and trousers by Hermès, hermes.com; Shoes by Hogan, hogan.com

And you were in bands, too, when you first moved to London…

Going back to your original question, about the age you are: if it was my brother, the eldest of five, and he had said: ‘yea, after university I’m just going to move to town, to London, and be in a band,’ my parents would have probably vomited. But that’s what I said I was going to do, and I remember my dad saying: ‘so how, actually, is that going to work?’ And I just sort of said: ‘it’s fine, don’t worry, I’ve got lots of contacts, I’ll do a part-time job and all that.’ Then I had a girlfriend, at the time, auditioning for drama schools, and I was helping her learn her monologues and she said: ‘why don’t you try?’ And I kind of went from there, and that was my way into the industry.

Do you still read philosophy?

I do, but I don’t read it in the academic way you do at university. Some of those texts, Kierkegaard and Nietzsche, they’re fairly dense. And, when you have waking babies, you need something a little softer. But I do think it informed my way of thinking, in a way, which sounds pretentious. The ability to have a little bit of analytical thinking helps in all forms of life, but especially in a world where you have to become the product. As an actor, you’re kind of peddling a product, and the product is you.

I think having an awareness of the fact that it’s important, but also not important, is good. Nowadays, you can be sucked into the world, and I think that can be detrimental to your sense of self. I’m kind of talking bollocks here, but behind the bollocks there's meaning. I guess it all gave me a little bit of grounding.

“I love the idea of retirement. I like the idea that you could do something and then leave it behind”

The Gentlemen is all about class perceptions as much as anything else. It’s something we are weirdly obsessed with in this country. Do you think about class a lot?

I’ve always been fascinated with the British class system and how it informs every asset of our unconscious social-economic structure, and how it continues to do that. The Gentlemen is fun and bombastic, but the heart of it – the idea of indentured wealth, class and money handed down over generations – is an interesting feature.

In this country, the burgeoning wealth gap is also part of that fascination with class. The richer the rich become, and the wider the gap has become, the more fascinated and repulsed people are by it. You have Succession, and White Lotus, and The Gentlemen in a different way. They’re huge, culturally, because we see these things every day, but not many of us get to touch it.

When we filmed at the make-believe estate of the family in the show, we used the Duke of Beaufort’s estate in Bath. It’s a beautiful estate. Apparently the Beauforts still own a massive percentage of Wales in landmass, and the Duke himself, if you Google him, various crazy Daily Mail stories come up. It was crazy to me that that is all still real. It seems so hyper-real in The Gentlemen, which is the design of the show. But there’s a large percentage of it that is totally real and totally fascinating.

Jumper by Dunhill, dunhill.com; Shirt by Tod's, tods.com; Trousers by Daniel W Fletcher, danielwfletcher.com; Shoes by Crockett and Jones, crockettandjones.com

At the centre of it all, as you say, is this big house. I think of novels like Brideshead Revisited and the film Saltburn and how we have this real interest in big, beautiful, creaking, foreboding houses. Why do you think that is? And would you ever like to be the Englishman in the castle, so to speak?

Guy loves the idea of the underworld mixed with the true English gent, and he’s got his own piece of pie, and shoots grouse – he loves it, and it’s very much a part of him. But, for me, I’m too awkward an Englishman, I’d feel too guilty. Even if I had all the cash in the world, it wouldn’t be for me. It’s all mixed into this question of the British Empire, which was almost the biggest empire in the history of the world at one point, and had this massive effect on global society, mostly for the worst.

The British, on the back of capitalism, created this empire, and then the dominance of the empire f*cked over millions and millions of people over the centuries. And that's why I’m fascinated by these country houses, because they represent a power – a huge, sweeping, romanticised power – that no longer exists in any way, but is still, somehow, close enough in our collective cultural history to understand or think that we’re somehow part of. Old Boris [Johnson] still thinks that we’re big-time ballers, and we’re obviously a tiny country. But there's still a pomposity within the English – myself included, subconsciously I’m sure – that we’re still a big empire. And that affects our understanding of our own country hugely.

The reason Boris Johnson was allowed to be a pretty awful leader – for such a long time – was his, sort of, cloak of poshness…

Yes. He cloaked himself in that old money, slightly tousled-around-the-edges eccentric thing. And there was a warmth to that, somehow, that let him get away with being a terrible leader. It’s amazing, really.

Jumper by Luca Faloni, lucafaloni.com; T-shirt by Zegna, zegna.com; Jeans by Studio Nicholson, studionicholson.com; Socks by Falke, falke.com; Shoes by Tod’s, tods.com; Watch by Omega, omegawatches.com

I read, in a previous interview, that you wanted to write a book. Is that still an ambition?

I love writing, but I’m also aware how hard it is to be really good. I never saw myself being an actor into retirement.

Why not?

Well, there are two things: One, I love the idea of retirement. I like the idea that you could do something and then leave it behind – have a finite career in your life. Life leads up to death, unfortunately, and beyond that: nothing. Or, at least, that’s what I believe – the black void. And, so, I enjoy the idea of not being defined by what you do for work.

This career is one where you are the product and you have to be in the limelight to a certain extent, and I think people get addicted to that and find it hard to leave behind – the elixir of whatever that is: fame, TV shows, magazines, people recognising you. I always thought I don’t want to be that person when I’m old and grey, but we’ll see. Eventually I’d like to not be in front of a camera, and I’m not sure what exact version of that will be.

The most obvious thing for an actor is to do something in the industry – behind camera, producing, directing. I was always impressed by those seminal actors who just peaced out. Joe Pesci’s back a bit, but I was always impressed by how he just said, ‘nah, I’m done.’ But, then again, you’ve got to pay your bills and your mortgage, so f*ck knows.

Do you think about death a lot?

Not death, but I’ve had experiences with it over my life, and, as a result, I’ve always been aware of mortality and what that means. And in the scariest way, it’s always been about: do we have enough time to do all the things we want to do in life? I’ve realised that life is incredibly short, and I mean that in the best way. I don’t believe in divinity afterwards, unfortunately, though, in some ways, I wish that did exist – and, so, all we have is the moment, and I’m aware we’ve got to live every moment because we only get one shot. So, it’s not so much a preoccupation with death but a preoccupation with mortality and the shortness of our time.

Is death a motivator for you, then?

I think it is. Death is a great motivator because there are lots of different things I’d like to experience in life, and that goes back to the idea of maybe not always wanting to be an actor, because there's a gamut of things I’d like to experience before we carp it. But, then, like everything, we get preoccupied with bullsh*t daily and you have to push yourself not to be preoccupied by the small things.

Having children, and watching them grow up really quickly, it makes you realise time goes really f*cking quickly, and you’re seeing it literally unfold before you, those moments you’ll never get back. So, I think mortality, and our brief time here, is definitely a motivating factor.

Cardigan and shoes by Loro Piana, loropiana.com; T-shirt by Slowear, slowear.com; Trousers by Dior, dior.com

Jumper and cardigan by Loro Piana, loropiana.com; T-shirt by Slowear, slowear.com; Watch by Omega, omegawatches.com.

Martin Amis died last year, and I remember reading in the obituaries that he was hugely preoccupied by his mortality. There was a line that was quoted from one of his novels, The Information, that said something about 'Cities at night, I feel, contain men who cry in their sleep and then say nothing,' which someone said was about middle-aged men and their thoughts of death. That struck me as a line that is so true – and, in a funny way, in writing about mortality in such a true way, Martin Amis might, in that line, have had a tiny shot at some sort of life after death. Is there some immortality available in that way, do you think?

As a young person, you’re looking for ways to literally and figuratively escape death. I think there’s probably a way to have a piece of your shadow cast a little longer than the length of your life. But, the reality of that is that it’s probably only for one or two generations. And knowing that is much more important, in a way. Consciously chasing to be remembered means you may miss what’s right in front of you – and, then, suddenly life’s gone.

James Dean – there’s an immortality to him, but he didn’t get to live life, he died young. The older you get, the more you realise that the people who are really going to remember you are the people in your life. Your family and your close friends. And, if you’re as present in their lives as possible, that is the way to live beyond death, as opposed to chasing something more grand and illusive. Martin Amis is, in most ways, a seminal writer. But, for me, the occupation is just in the here and the now.

Jumper by Luca Faloni, lucafaloni.com; Jeans by Tiger of Sweden, tigerofsweden.com; Slippers by Loro Piana, loropiana.com

With special thanks to:

Photographer: Will Corry

Photography assistant: Andrew Edwards

Stylist: Zak Maoui

Styling assistant: Freya Anderson

Grooming: Nadia Altinbas

Creative direction: Danielle O’Connell and Freya Anderson

Videographer: Nefelie Pourgouridou

Post-production: Lucie Silveira

Location: The Berkeley Hotel

Want more cover interviews? Here's Callum Turner on his pinch-me career highlights so far...

Become a Gentleman’s Journal Member?

Like the Gentleman’s Journal? Why not join the Clubhouse, a special kind of private club where members receive offers and experiences from hand-picked, premium brands. You will also receive invites to exclusive events, the quarterly print magazine delivered directly to your door and your own membership card.