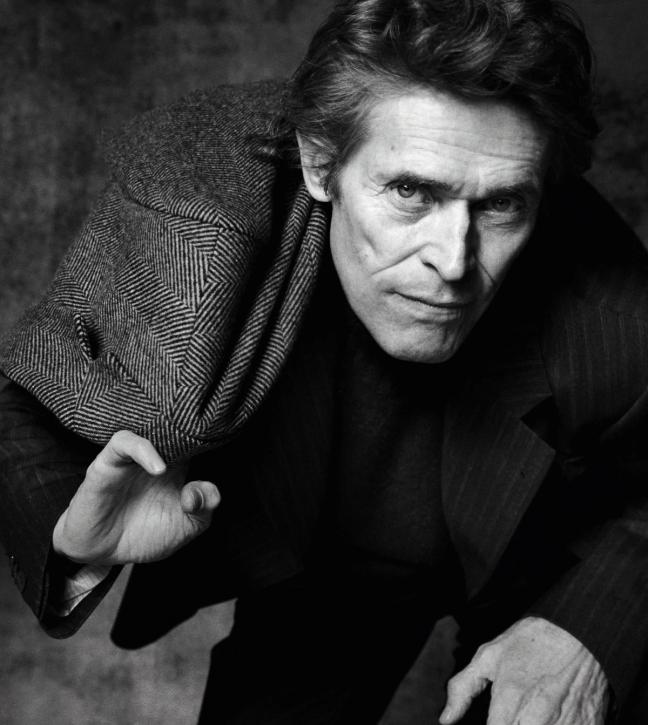

“I’m not that aware of it,” says Willem Dafoe — speaking freely, candidly and somewhat surprisingly about his own face.

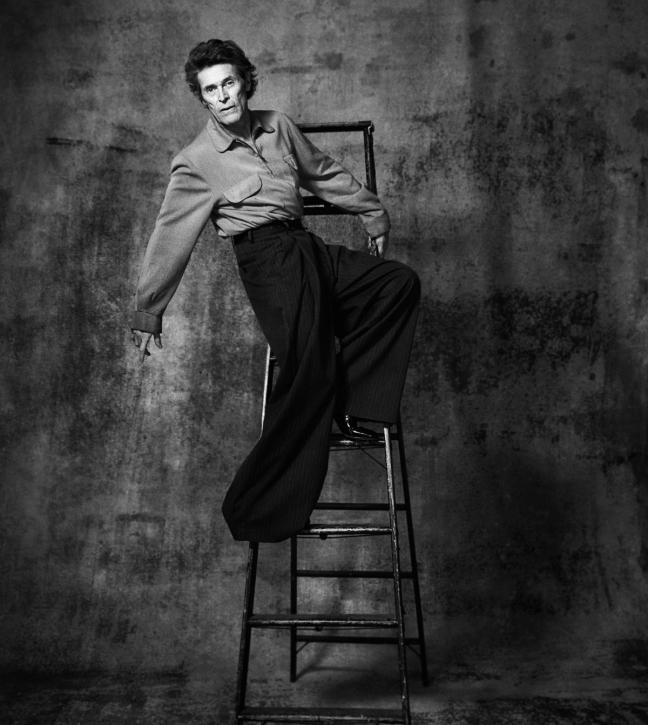

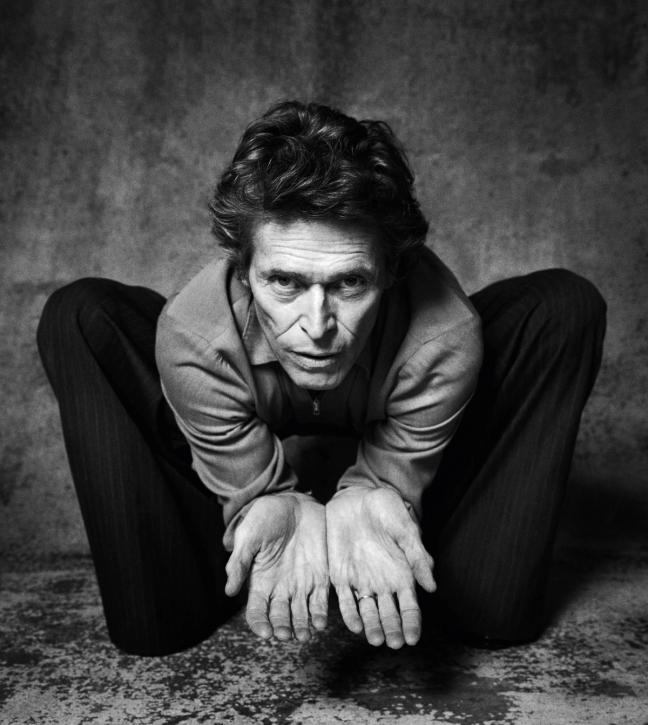

It’s a strange sentiment. It would be coming from anyone. But coming from Dafoe — a man with a visage so striking you could recognise it from fifty paces — it’s downright baffling. Just look at him. Those knowing, misty grey eyes. The menacing, mesmerising stretch of a mouth. Cheekbones so sharp it’s a wonder he can fly commercial. Surely a face this remarkable would be considered an actor’s greatest asset? But no. Implausible as it may seem, Willem Dafoe just isn’t that aware of his face.

“People tell me about it,” he ponders, softly chuckling to himself. “And I know that people recognise me easily. So I must have a pretty singular look, I suppose. Who knows? What I do know about my face is that it is very, very expressive.”

Another wild understatement, but let’s see where he’s going with this.

“I sometimes see pictures of myself, out of the context of acting,” says Dafoe, pausing mid-thought. “You know, red carpet pictures, things like that. And I just look so ugly, I look so grotesque and weird. My face expresses things that I don’t even intend for it to express sometimes. It’s got a mind of its own!”

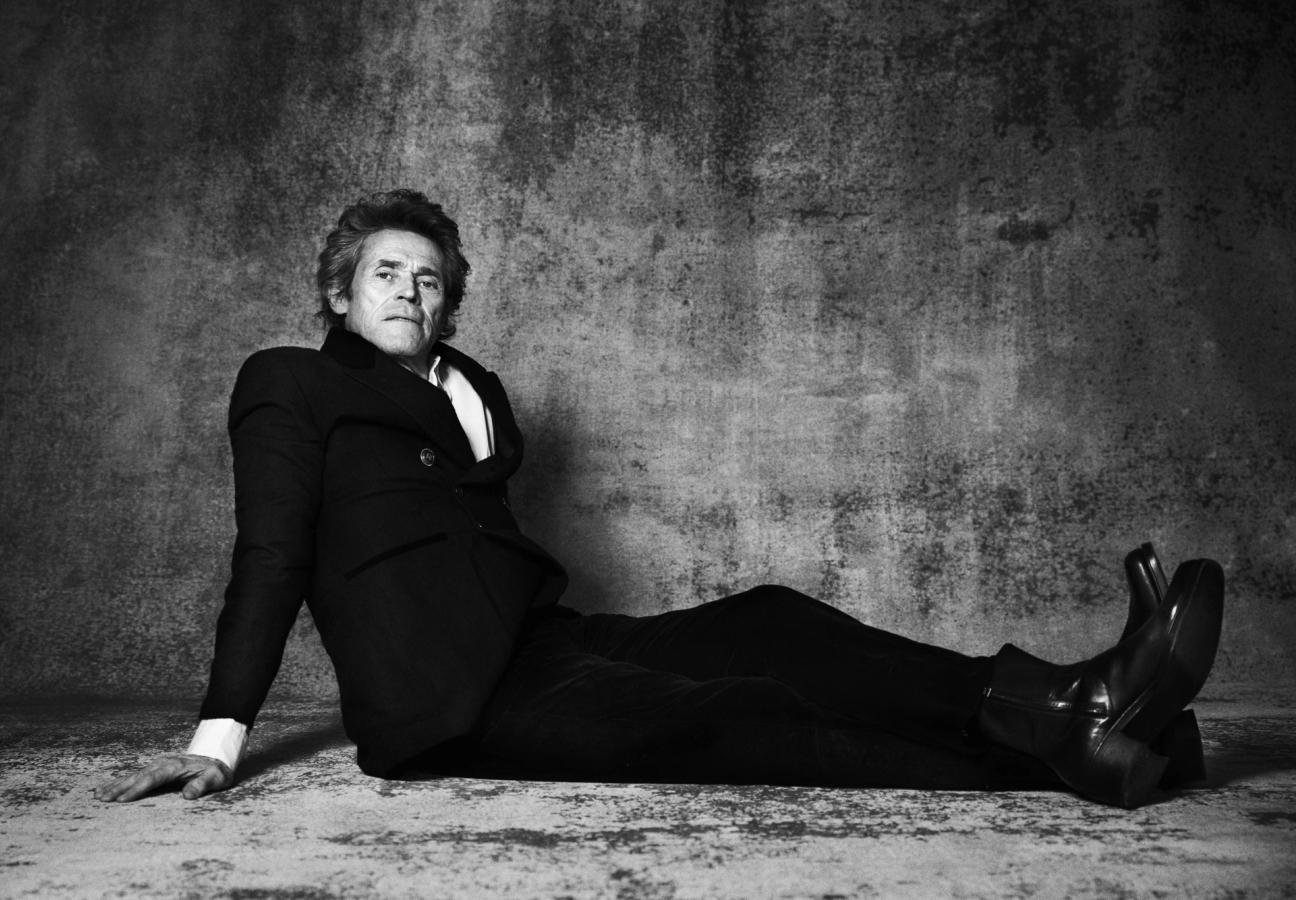

Thankfully, Willem Dafoe and Willem Dafoe’s face have used this innate recognisability to their joint advantage. To date, the actor has appeared in well over 100 films, and his prolific career can be charted through the cracks and comments — some nice, some not so nice — that those in the industry have made about his looks.

Take Dafoe’s first-ever screen role. The year is 1979, and shooting on Michael Cimino’s western epic Heaven’s Gate is well underway. Dafoe, the movie buffs among you will recall, doesn’t appear in Heaven’s Gate — and that’s because he was fired from the project. Why? Cimino approached Dafoe for a small role in the film because he presumed the actor had Dutch heritage due to his “ethnic face”. On set, when it became apparent that Dafoe couldn’t in fact speak Dutch, he was swiftly, and unfairly, axed.

But Dafoe had got his foot — or should that be face? — in the door. Hollywood would soon call again. And again. And again.

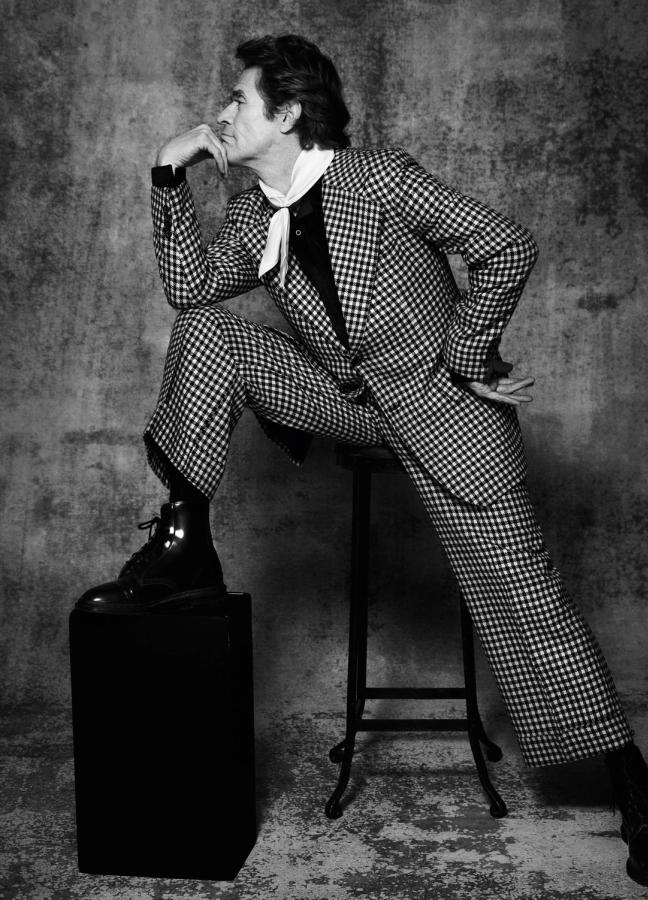

In fact, in the intervening decades, Hollywood has called many, many times — as have independent filmmakers, foreign studios, animation houses, video game developers and scores of theatres. On the big screen, Dafoe has taken roles in Platoon, Mississippi Burning, Born on the Fourth of July, The English Patient, American Psycho and Shadow of the Vampire. He flew into The Aviator for a cameo, swung into the Spider-Man trilogy as the villainous Green Goblin and dipped his toe in voiceover work with Finding Nemo. He’s taken on John Carter, John Wick and narrated films from Vox Lux to The Great Wall. He’s been Oscar-nominated several times, for playing characters as wild and disparate as hammy vampires, Floridian motel managers and Vincent van Gogh. The man is a chameleon — and has managed to become one despite having Willem Dafoe’s face.

He may come across as something of an acting maverick, but Dafoe is startlingly understated about his career — even as it eases up to legacy status. “No, I’ve never thought of myself as a maverick,” he says, measuredly. “Not in the film community at least. I don’t live in LA and I don’t do a lot of shoots in studios. If you look at my filmography, you’ll see that I travel a lot. So I’m not so much a maverick, as maybe a migrant.” He laughs again; a throaty, heartfelt laugh.

“I’m really just making it up as I go along,” the actor adds. “I’m not that career-driven. I mean, I consider career to the extent that I’m always looking to create new opportunities and do the things I like to do, but I’m actually quite simple-minded.”

The new opportunities keep coming for Dafoe, who continues to flit and skip between time periods, genres, settings and characters like the maverick he insists he isn’t. On his long, varied roster of roles, you can count conniving politicians, seven-foot aliens, priests, assassins, supervillains and Japanese supernatural spirits. Dafoe’s work on screen is so unpredictable that he simply looks like a man terrified of repeating himself.

“Actually, I never worry about repetition,” he counters. “In fact, I think repetition in this line of work is overrated. Nothing’s ever the same anyway; the target is always moving. It’s like when someone says they’re bored — in my opinion, the responsibility for that lies with them. The world is always swirling, and it’s only boring if you don’t take notice. But if you’re there, watching the rise and fall of the swirl, it’s never dull. I’m never bored.”

“I’m really just making it up as I go along..."

Thankfully, with Dafoe’s own swirling career to watch, neither are we. In 2019 alone, the 65-year-old added seven more films to his long list of roles. These included Motherless Brooklyn, which saw Dafoe directed by Edward Norton, playing a key part in a film noir set on the corrupt streets of 1950s New York. Togo, a historical epic, had Dafoe bringing yet another real-life character to the screen: this time, Leonhard Seppala, a Norwegian sled-dog breeder whose heroic, antidote-carrying, frostbite-battling efforts saved the Alaskan town of Nome from an epidemic of diphtheria in 1925.

While discussing Togo, Dafoe reveals that he relishes playing historical figures. But unlike some of his contemporaries, he’ll only do so if they are made the focus of the entire film. Bit-part real-life roles are tricky, he says, as they don’t give you the chance to fully sink into the character. Happily, he had an entire shoot to step into the snow boots of Seppala — not to mention a face suitably ‘ethnic’ enough to convincingly play the Norwegian.

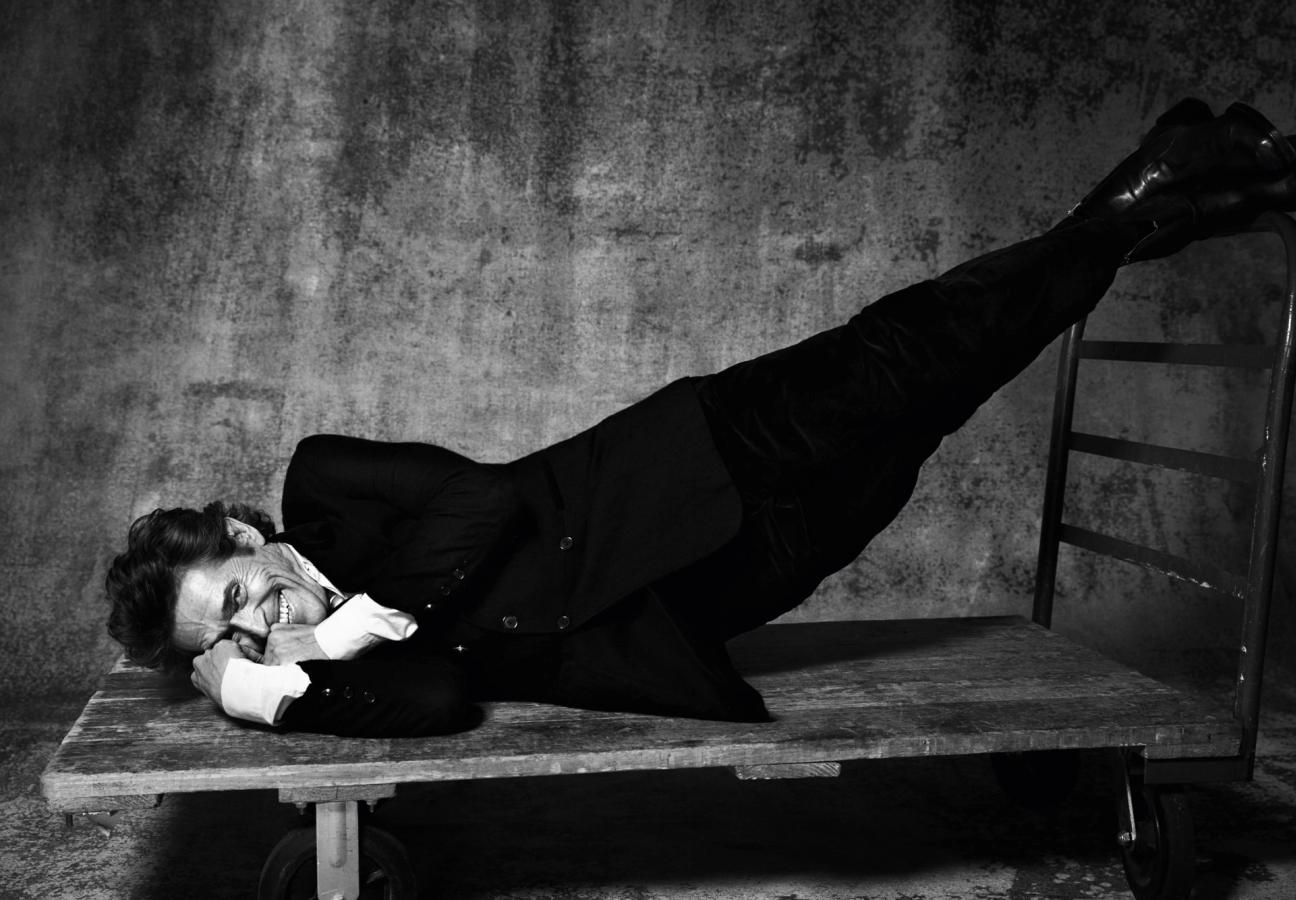

But for all the gumshoeing and dog-sledding, perhaps Dafoe’s most hyped film of 2019 was The Lighthouse. This visionary horror is a chilling coastal tale of misery, mermaids and vengeful seagulls. Shot in black-and-white and filmed in a square format, Robert Eggers’ second crack of the period horror whip — after 2015’s critically-acclaimed The Witch — is unsettling, enthralling and feels startlingly fresh. But it didn’t feel as pioneering to make as the final cut may suggest, Dafoe comments.

“Although,” he backtracks, “the process of doing it, while not being singular, was still special. Just in the respect that all the details and set-ups were so precise. And, of course, we were working in tough conditions, working with nature. But, come what may, I’m the kind of actor who likes to stay on set. I’m like a little kid like that. I like to be where the action is — I never want to miss out on anything.”

“And what was peculiar about The Lighthouse,” Dafoe explains, “was that, even when we were inside, in these buildings that were very rickety and had no heat, it still felt like camping out. I enjoyed that. It was an adventure.”

It certainly was. And Dafoe took his part in the Oscar-nominated two-hander — with a dazzlingly good, dazzlingly moustachioed Robert Pattinson — very seriously. After each day filming along the Canadian coastline, Dafoe watched his younger co-star and the crew retreat to the warmth and hospitality of a local hotel. He, however, opted to stay alone, in a small fisherman’s cottage. Cut off from all contact, learning to knit and perfecting his Robert Newton-style rasp, it all sounds, dare we say it, a little method.

“Would I call myself method?” asks the actor. “Not by the normal definition, I don’t think, no. I mean, I’m always changing my acting. The reason I always stay on set is because I always like to practice. But that’s more so I can hang out and see what’s going on.”

It’s a question that seems to stump the 65-year-old. During Dafoe’s time in the industry, what it means to be ‘method’ has changed so many times that nobody truly knows what it means any more. The actor himself believes that ‘method’ acting usually points to a more stringent Actor’s Studio approach to the craft, using techniques such as substitution, affective memory and living as your character for the duration of a film.

“And I was never really trained in that,” he continues, chewing over his words. “I don’t even respond to that. I’m more like a dancer; I think in terms of everything, doing things and reacting. Don’t force it. If you don’t force it, you’ll find a purer reaction. Because, as an actor, you’re not meant to be selling a psychology; you’re not telling a story by punching buttons. You’re having an experience, and you need to approach that in good faith and an open way. That’s when things really start cooking.”

It makes sense that Dafoe couldn’t be a method actor. He’s not Daniel Day-Lewis, releasing two or three drama films every decade (coronavirus permitting, he’ll appear in at least that many in 2020 alone). He’s Willem Dafoe, dropping the most recognisable, distinctive face in cinema into up to eight films a year. But all this talk of ‘method’ has rattled something inside the actor, and he’s keen to carry on down this path.

“I went to a state university in Wisconsin,” he begins, seasoned storytelling audible in his words. “This state university had an acting program, one which I stayed in for two semesters. I took all the acting courses I could, I took all the movie courses I could. But then, all the other basic requirement courses came up. And, as I had ants in my pants, I just upped and walked out so I could start performing.

“But that’s kind of sad,” he presses on, after a pregnant pause. “Because it means I’ve never really had a proper formal education. Instead, for all of my life, I’ve just kind of been playing catch-up with basic things, like history or whatever.”

Dafoe is still a fiercely intelligent man. Moving from world to world, role to role, he’s certainly learnt more than most of us do in our nine-to-fives. He’s still learning — stumbling upon one of his most rewarding experiences just two years ago.

In 2017, Dafoe took a gamble on slice-of-life drama The Florida Project. He was one of the only actors on set who had ever stepped in front of a camera. Working with new, untrained talent brought out new colours in Dafoe’s performance and, for his nuanced, beautiful turn as motel manager Bobby, he was nominated for his first Oscar in almost two decades.

“It was just a challenge to not be an actor,” shrugs Dafoe. “And I liked that challenge. Because you still have your craft and experience to lean on, but you’re just trying to be a human being. And, especially when you’re dealing with people who don’t have that craft, you have to approach performing in a different way. You have to get on their wavelength. And that can be very rich, because often there’s not the corruption that happens in people who have been performing for a long time.”

It’s an interesting take. But even some of the big Hollywood blockbusters Dafoe has taken on, films populated with highly-trained casts and backed by the might of vast studios, have been gambles. After all, for a man who works so prolifically, there must be a higher chance of encountering risks. Does he have doubts?

“There are always doubts, yes!” cries Dafoe. “Because, when you initially sign onto something, you never know where you’re going to end up. You’ve just got to live with the reason you’re doing a role. And, even if a movie fails, if you had a good reason for trying, if it was a noble attempt to discover something, do something special that you thought might take you to a place that might be fruitful — and then none of that happens, you can’t beat yourself up about it. Films are so collaborative that sometimes, even if you do your best, they just don’t really work.”

Of course, there are also films that stumble upon problems even after they’re in the can. When the devilish Dafoe played the Son of God for Martin Scorsese in The Last Temptation of Christ, few could have predicted the hellish controversy, allegations of blasphemy and widespread boycotts in which the release would be mired. The thorny response even took the measured Dafoe by surprise.

“It was just disappointing,” he says, deflatedly. “Because I thought it was a beautiful film. And in a world of slasher films and porn films, it was a movie about spirituality. A sincere study about the human aspect of the divine, and the divine aspect of the human. It was a creative exploration, an invitation to challenge your faith. If your faith is so weak that a movie taking some liberties can throw them into question, then you’ve got some pretty shaky beliefs!”

That ill-fated 1988 epic wouldn’t be the last time Dafoe would court controversy. His longstanding collaborative partnership with the provocative auteur Lars von Trier has also raised many eyebrows and stepped on many toes; most notably with the 2009 experimental horror film, Antichrist. The film, one Dafoe remembers as “an incredibly rewarding fight against an oppressive, male-dominated society”, coaxed both boos and applause from the audience at its Cannes Film Festival premiere. But this, Dafoe laughs, only epitomises von Trier’s reputation as a “passionate, if a little troublesome, filmmaker”.

"If your faith is so weak that a movie can throw them into question, then you’ve got some pretty shaky beliefs!"

Even with such a dedicated filmmaker as von Trier at the helm, production on Antichrist didn’t run smoothly. The project was stalled when Dafoe’s co-star, Eva Green, was suddenly forbidden to take part in the film by her agents. Dafoe had no such trouble signing on, despite an unsettling script full of acrimonious acorns and a self-disembowelling fox. Has the actor ever encountered pushbacks from his own team?

“You know, there’s always someone who wants to give their opinion,” the actor reasons, “but I like to think that it’s always a fluid conversation. If I feel strongly about a role — but they don’t think it’s a good idea — we’ll usually talk. They know me well enough to know that, if I stand firm, and give enough reasons for why I want to do it, they’re not going to say don’t take a role. They can advise, but ultimately it’s my choice.”

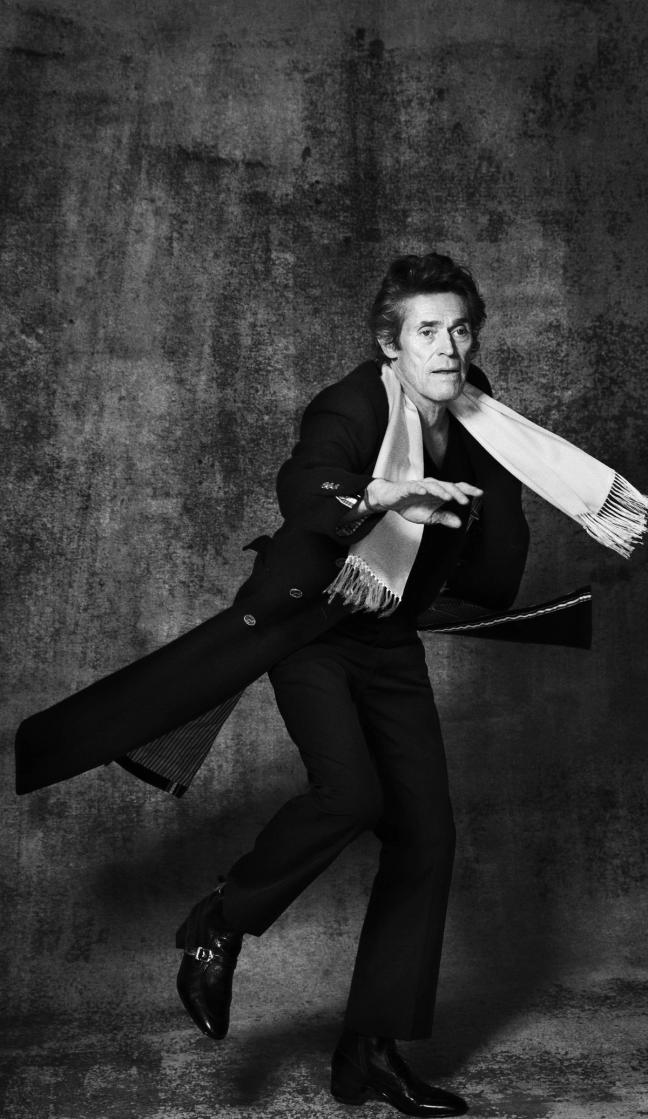

And Dafoe’s choices have been far from shy or safe. Antichrist is certainly not alone in its exploration of serious themes, taboo-treading and deep dives into the psyche — the brine-spattered, stormy-skied The Lighthouse stands testament to that. But while the actor, with his constantly furrowed brow, looks like he could be permanently traumatised by his experiences, he wants to reassure that he has a coping strategy — and couldn’t care less about his frown lines.

“Some of the characters do worm into your head,” Dafoe concedes, “but I can leave them behind. You create new experiences, you grow up every time. Of course, some roles stick with you more because, as life experiences, they’re more substantial and they affect you more. I mean, I’ve played van Gogh, I’ve played Christ, I’ve taken on very physical roles, I’ve shot an entire movie on location in Auschwitz. But you always then move onto the next project.

“And,” he quickly adds, “I really do believe that, inside of us, there is the whole world: all people, all characters, all possibilities. And they can all come out — but only when the situation presents itself. Take away that situation, the inspiration, and they’re going to go back in. They’re going to hide back behind whatever personality you’ve constructed for yourself, whatever personality helps you function in society.”

Despite his earlier protestations, it sounds like there’s at least a little method in the maverick. And, while he may hide any remorse or regrets well, Dafoe’s obviously got his demons. But that’s something we should really be glad about: it makes his playing of them that much more enticing.

And the actor has been darting across to his dark side since he first became a film star. In a largely forgotten 1984 neo-noir, Streets of Fire, Dafoe played the leader of a nefarious biker gang. Critic Janet Maslin of The New York Times described him as having a “perfectly villainous face”. Despite his proclivity for playing evil early in his career, it’s a description that still doesn’t sit well with Dafoe 35 years on.

“I think,” he quietly considers, “that sometimes, people get very lazy when they’re under pressure to describe things. I think it’s a weakness in our culture — that we always refer to things by other things. People just don’t speak directly about things any more. Even sometimes in screenplays, I find that rather than describing something well, people will describe one thing by likening it to another thing — as if they think that makes it more specific.

“When, actually, that only clouds the image. So saying I have a villainous face shows an inarticulateness. Villainous? That’s not what they actually see.”

Dafoe is riled. But then, it follows that nothing would anger him like inarticulateness. After years spent carving new niches in the industry, experimenting with acting and making his own truly indelible mark on cinema, being confronted with comparisons must sting. But it’s a fool who would try to liken Willem Dafoe to anything or anyone else anyway — because simply nothing is.

Looking for more actor interviews? James Norton wants to be a Bond villain…

Become a Gentleman’s Journal member. Find out more here.

Become a Gentleman’s Journal Member?

Like the Gentleman’s Journal? Why not join the Clubhouse, a special kind of private club where members receive offers and experiences from hand-picked, premium brands. You will also receive invites to exclusive events, the quarterly print magazine delivered directly to your door and your own membership card.