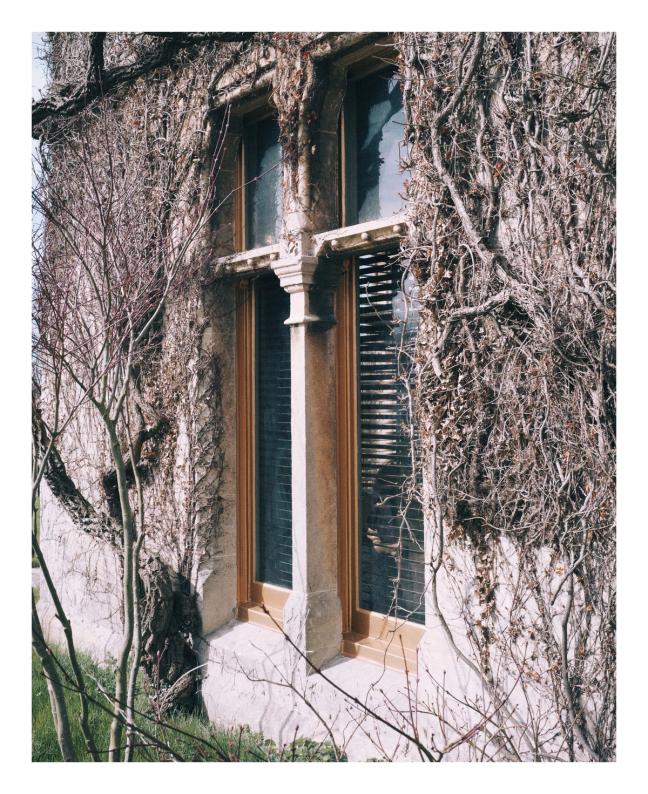

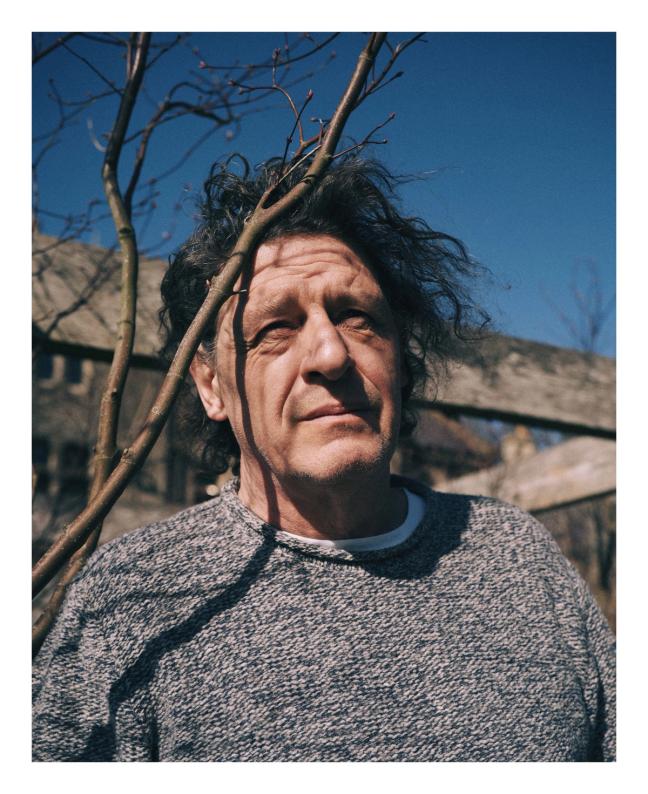

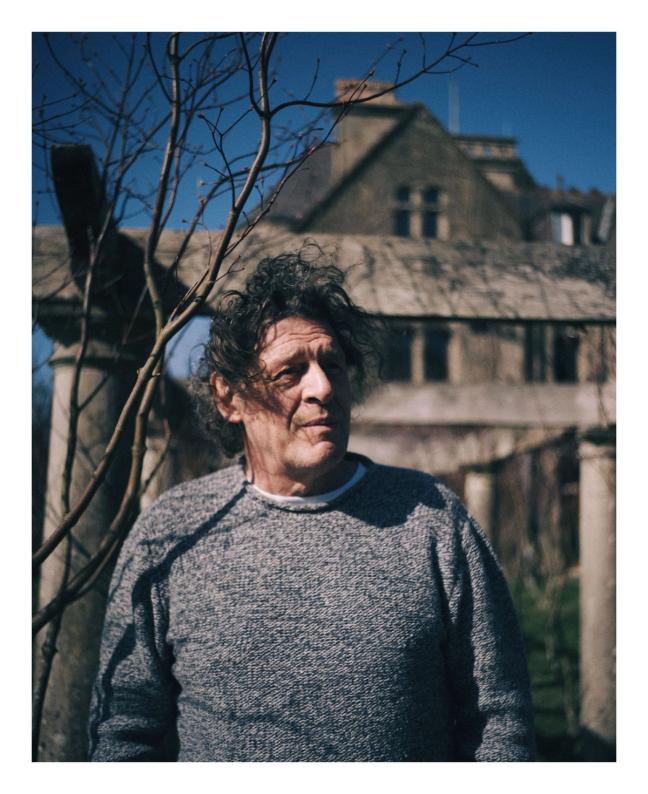

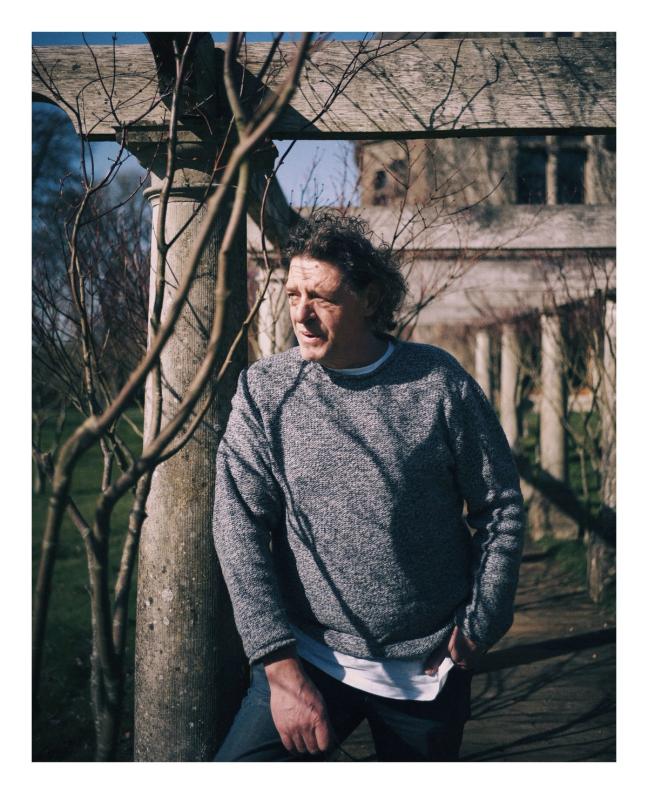

I’d like to say I interviewed Marco Pierre White earlier this week, but I didn’t. I just turned up, shook his hand, and Marco did the rest. When we first arrived, the house looked empty — a Victorian Gothic pile at the crest of a hill, preceded by a long, winding driveway, flanked to each side by stacks of chopped wood. The ivy was bare on the brickwork, and the taxi driver said: “oh, the big house? You should have said” as we crunched up the gravel. The front door swung slowly on its hinges, opening into a dark hallway paved with flagstones as big as graves, and nothing inside stirred. There had been no publicists or agents involved — just a few short calls to Marco’s Nokia 3310 in the days prior. It seemed possible at that moment that we had got the wrong date, if not the wrong end of the stick entirely. And then, as if summoned from the ether, he appeared — perched on a stack of wooden palettes, staring out over the sweeping vista of the Avon Valley like the high priest of steak. Big, broad; a lock forward in a sailor’s jumper; master of all he surveyed — and a vocal advocate for dry-stone walling.

“We’ve just had these ones done,” he says, guiding me instantly into the big garden before I can even introduce myself. “And we’re putting in the estate fencing right now, and laying down these railway sleepers for a path — you know how fucking hard it is to cut up railway sleepers?” There’s a huge pond being dug up ahead, and a small orchard of little trees dotted across a paddock below the main house. “I hate parasols, so we’ll use these for shade,” he says. (The finished product will be a handsome country hotel and restaurant, by the way — but it’ll be Marco’s house, too. “Like a stately home, with a velvet rope dividing off the private quarters,” he says, crackling into a deep laugh. “Me, Lord of the Manor!”)

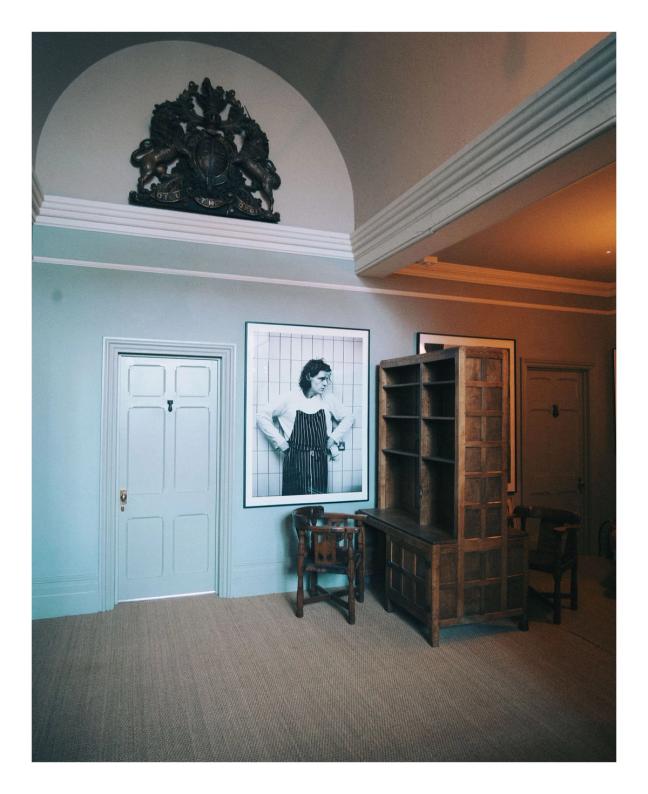

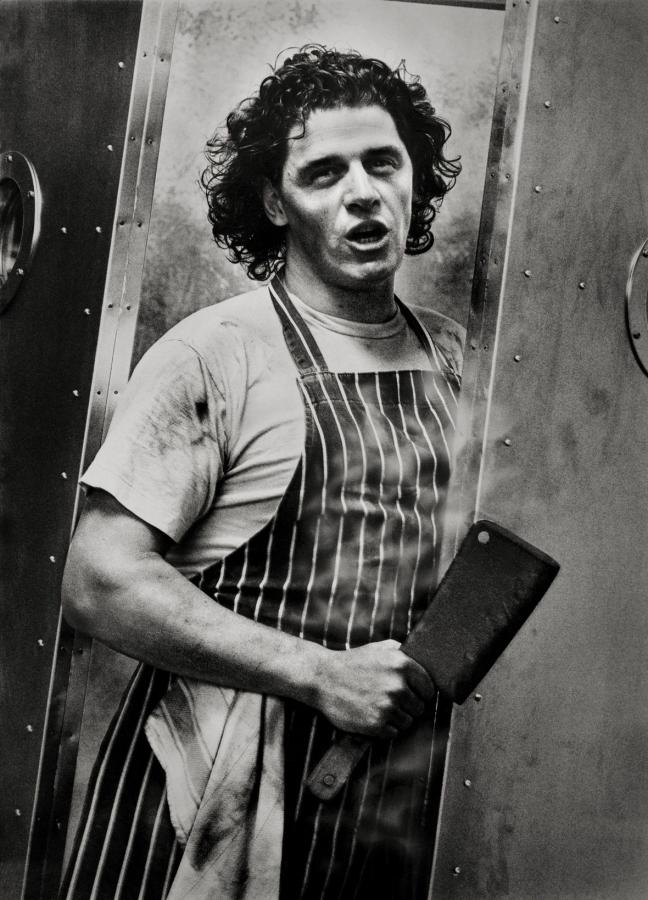

And then we’re off. For the next few hours, we’re locked in to Marco FM — a whirlwind, riotous broadcast about the house and the great chef’s life. We swoop past vast black and white prints of that furious young man with the cherubic curls; pause to admire the interior metalworking on a 1920s fridge; stop to examine some lizard specimens in a cylindrical glass jar; sip from a bottle of 1945 eau de vie suffused with a dead silver viper. Marco is big and generous, in both hospitality and conversation. He is a juggernaut paused at the top of a steep hill, needing just the faintest push to get rolling, roaring, flying, on any and every subject. His voice modulates from a broad Yorkshire grin to a kind of gravelled Shakespearean whisper, as he draws you into the heartfelt conclusion of a tale from his Italian childhood or the white heat of a basement kitchen. Each sentence is studded with a curt, reflexive “YES?”: a relic from the service pass, and a clever trick in its own right — you agree with the man before you’ve even had a chance to say anything. And he is a philosopher-cook, if such a thing exists — a steak is never just a steak; salt is more than simply seasoning; a fig is love and death.

“When you walk into a three [Michelin] star [restaurant], the emotional impact on you should be like taking the most beautiful girl to bed for the very first time,” Marco begins, leaning back on a deep sofa, the sunlight griddled by French blinds. “You’re intimidated by her beauty. But your fear has now been dissolved by excitement, and the thought of love.”

“And secondly: it should almost feel like going to church. You should bow.” From another chef, that might seem trite. But for Marco, food and restaurants do genuinely seemed to have been a salvation. The stories from his early career are inflected with moments of divine intervention and Old Testament colour; the gospel according to Marco. On the day he made the teenage pilgrimage to knock on the door of the Box Tree Tree in Ilkley — then one of the finest restaurants in the country — and asked for a job, another chef had just handed in his notice. “If I had applied a day later, I would never have got the job, would I?” Months later, after missing the last coach back to his hometown of Leeds, Marco stumbled, quite literally, into the front window of Le Gavroche — and wandered the streets all night until he could meet with its fearsome chef-patron, Albert Roux. “I didn’t know it then, but ‘Le Gavroche’ means ‘street urchin’”, he says. “And that is what I had become. And Albert Roux gave me my start.”

“Success is born out of luck. Luck is being given the opportunity. It’s awareness of mind that takes the opportunity.” Marco saw his chance and ran with it. The alternative, he says, was too horrific to bear.

“Everywhere was tough at that level. Emotionally and mentally, those kitchens were very tough in those days. But I was ruled by that fear of failure. If you lost your job, you had to go back home. I would have to go back to the council estate. So I worked so hard. I didn’t care about tiredness.”

It paid off. After Le Gavroche came La Tante Claire under Pierre Koffman, and then Le Manoir in Oxfordshire with Raymond Blanc. Soon, the leoline protege has branched out on his own — first with the Six Bells public house on the Kings Road (alongside right-hand-man Mario Batali), and then with Harvey’s, down on Wandsworth Common. Opened in 1987, it was the making of the man in many ways: the place where Egon Ronay, the great restaurant guide writer, first convinced him to use his real name professionally — not simply Marco White, but Marco Pierre White: the Italian-French-English genius; passion and history and pragmatism all at once. At Harvey’s, Marco won a Michelin Star almost immediately, and by the age of 32 he had scooped up two more — the youngest chef in history, at that time, to achieve such a feat. I ask him what he remembers from that period, and think of the YouTube clips and photographs I have seen of him at that age: a barking, winking, simmering Romantic at the stove, towering and smouldering over a baby-browed Gordon Ramsay, and smoking constantly. People like to use the phrase enfant terrible about young Marco; they call him “the first rockstar chef”. Is that picture accurate?

“I went out with attractive, aristocratic girls. I cooked in the kitchen. I kicked customers out — I was the perfect product for the Daily Mail at the time.”

“Here was a boy who had a certain look. Long hair — that pre-Raphaelite look,” Marco says. “I went out with attractive, aristocratic girls. I cooked in the kitchen. I kicked customers out — I was the perfect product for the Daily Mail at the time.”

“But I was very hard working. I worked over 100 hours a week, for many, many weeks. I worked six, seven days a week. I like work. Work is the greatest painkiller known to man. Gastronomy is the greatest form of therapy any misfit can be exposed to.” And what was the pain he was trying to subdue?

“I suppose what I was trying to do, on reflection of my life, was to overcome the death of my mother at the age of six. Because I watched my mother die in front of me. I watched the ambulance men carry her away. And my father was very silent. It was like my mother never existed. He eradicated her. But that was his way of dealing with her. For me, all that pain within me had to be released. And hurt manifests itself within us as anger, and you have to release it from within you.”

“Great chefs have three things in common. Firstly, they accept that mother nature is the true artist — and they are just the cook. Secondly, everything they do becomes an extension of themselves. And thirdly: they give you great insight into the world they were born into.”

I ask Marco about his own childhood — that council estate outside Leeds in the 1960s. “I come from a very real world. A world where we were too poor to have tins. We had to peel potatoes. We had to peel sprouts, pod peas. I used to go down to the butcher’s with my father, and he used to inspect four, five joints of beef, and have great discussions with the butcher about them.”

“I used to sit on the side, watching my mother make risotto, because she’s from that region, Veneto, in Italy. And I would watch as all the women — my nonna, my two aunties, my mother — all prepared the vegetables for the minestrone. Watching them harvest the figs — the farmer, coming over, and giving my mother and my nonna figs — and watching my mother tearing it in half and giving me half…” his voice slopes down to a crackling whisper. “And so today figs are one of my favourites. And my mother’s favourite biscuits as a young lady were fig rolls. It’s about the romance of food.”

This type of talk seems entirely at odds with the high-minded, high concept cuisine of today; molecular gastronomy and minuscule precision; mind not heart. Marco’s squash racket hands gesticulate wildly as he talks about salting steak to within an inch of his life, and flooding a pasta sauce the night before with an ungodly amount of basil. You can’t imagine him holding a pipette. Before we start recording, he looks pained by previous dining experience at various Three Starred restaurants around the world — wincing in memory of a smoked cube of lamb the size of his little finger nail; about flowers arranged with tweezers on the plate; about lukewarm sauces in squeezy bottles, and chefs who have time to stand tableside and sermonize on their ‘inspiration’ for the oyster starter. “The world has changed. The golden age of gastronomy has gone. The romance has gone,” Marco says. “I belong to the old world, really,” — an age of Escoffier, white table cloths, silver-service, burned fingers.

“There’s two types of chef. In fact, there’s two types of men, really, in life. There’s the hungry ones — and there’s the greedy ones. I mean hungry for life; and greedy for money. It’s not for me to say which one I am. It’s for others to choose who I am. But everything I did in my life is by default. Remember: I made my name by what I put on the plate, not by doing TV. I only did TV after I won my three stars. And by hanging up my hat and saying: ‘no more’… now I don’t have to live a lie.”

It often comes back to this. The moment when Marco walked away. In 1999, at the age of 38, he handed back his Michelin stars and left professional kitchens for good. “Walking down that road to Michelin, there’s no emotional growth,” he explains. “You’re stunted, because all your energies go into your food, and not the development of yourself.”

“[At Michelin]The business is making tires. They make their money out of making tires. And let’s be very honest, they make very good tires. Their knowledge of tire-making is greater than their knowledge of food. So why did I give my stars back, why did I walk away? No disrespect to any of them. But I was being judged by people who had less knowledge.

“So I had to hand back my stars. I had to walk away. And what I did was exactly what I did when my mother died. I turned to nature. I went back to the English countryside…. I relived my childhood. And I realised mother nature had been my surrogate mother, all along. It gave me the time and opportunity to invest in myself. To relive the childhood I never had.”

“My achievements as a cook don’t mean anything to me. They were just stepping stones to where I wanted to be in my life. And we all need stepping stones.”

And then we’re up again — marching across the garden as Marco simmers briefly for his portrait; pausing at a black and white photograph of his mother in the living room; staring out in rare silence over the valleys down below.

Read next: Tom Odell talks money, mental strife — and monsters

Become a Gentleman’s Journal Member?

Like the Gentleman’s Journal? Why not join the Clubhouse, a special kind of private club where members receive offers and experiences from hand-picked, premium brands. You will also receive invites to exclusive events, the quarterly print magazine delivered directly to your door and your own membership card.