The history of the wall game

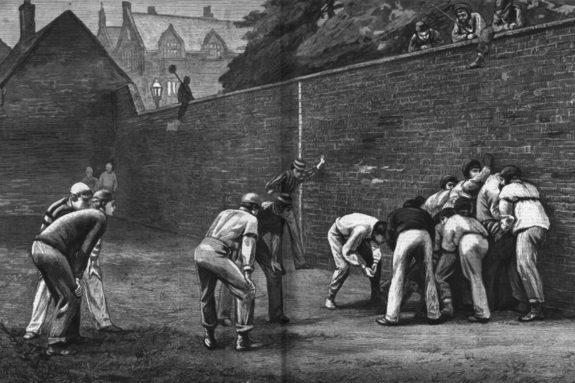

Every game has to start somehow. Rugby, for instance, famously got going in 1823 after a schoolboy William Webb-Ellis picked up the ball and ran with it during a game of footy. You can see how golf might have had its lightbulb moment when a bored rambler tonked a dod of sheep-shit into a rabbit-hole with his shooting-stick. But the Eton Wall Game? That one defeats the imagination. Did some football player grab the ball, run off the pitch to the nearest brick wall (in this case a specific brick wall in Eton College), kneel on it and encourage his team-mates to don gardening gloves and form a semi-vertical scrum on top of him before burbling about furking?

Put it this way: it may not be entirely a coincidence that the most important Wall Game match of the year takes place on St Andrew’s Day, at the height of the magic mushroom season. Yet this bizarre game — which has been played since 1766, so is older than rugby (which Wikipedia has the cheek to say it resembles) — is Eton College’s greatest, most eccentric and least portable gift to the world.

So, the rules. These will not be easy to explain in the space we have available. They are not easy to explain full stop. Few if any of the players involved, if they’re honest, have a secure grasp on them. But, roughly, there’s this big brick wall, right? It’s about 100 metres long. At one end of it there’s another perpendicular wall with a door in it; at the other end there’s a tree (or, was, until some unsporting locals burned it to the ground a few years back.) Oh, and there’s this white line that runs along the ground about five metres perpendicular to the wall. The area between this line and the wall is the playing area of the game and it’s called the “furrow”.

The game gets underway when one member of the team kneels on the ball down against the wall, and everyone else piles on top of him, sorry, “forms a bully”. Then the game starts: everyone pushes and heaves and knuckles their opponents in the face or, if they can’t reach an opponent, a member of their own team. All this knuckling is fine, but a referee will be peering into the bully in the hopes of telling people off for outright actual punching or an obscure crime called “furking”. (Eton College’s own website says, not without pride, that “few sports offer less to the spectator”.)

Anyway, at some point the ball may emerge from this roiling pit of violence, in which case “lines”, a player hovering outside the bully, will attempt to hoof it further along the furrow and the bully will reform further up. The idea is that by a combination of this method and brute shoving, you will eventually end up with your team in possession of the ball, and the bully in “calx” at your opponents’ end. Calx is a marked-off area – think of it like a penalty area – in which scoring becomes possible.

Someone has to lift the ball off the ground with his foot and hold it against the wall (all this amid the aforementioned roiling pit of violence), and another member of his team touches it with his hand and yells “Got it!” If the umpire agrees —“Given!” — then yay! A “shy” has now been scored. It is a pretty rare event.

Also, all hell breaks loose because in the moments afterwards the team that has just scored is now entitled to hurl the ball in the direction of (depending which end they’re at) that door or that tree in the hopes of scoring a goal. This is an even rarer event. In fact, a goal was last scored in the St Andrew’s Day wall game in 1909.

Michael Beloff QC, an Old Etonian who has gone on to become one of our foremost authorities on sports law, remembers the game with a representative mixture of affection and bemusement: “I witnessed six annual contests to resolve the perennial question whether well trained brain, with home advantage, could defeat untrained brawn,” he says. “Alas no answer was given during my time since all matches ended with nul points either side. For me the climax of the occasion was the eve-of-match march of the squad of scholars round the statue of Henry V I as they sang to solicit the founders blessing…”

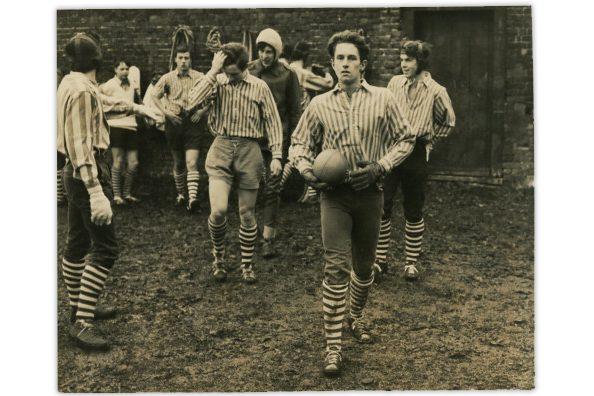

This St Andrew’s Day match is the big event — it’s played earlyish in the morning, and it’s played between College (the scholars’ house) and Oppidans (everyone else: fee-paying oiks, in other words). College has a talent-pool of only 70 boys (about thirty in the top two years) versus the 1250-odd Oppidans. The reason they don’t get pasted is that a) nobody tends to score a shy, let alone a goal and b) the wall belongs to College, so the Oppidan Wall have to ask permission to practise, which they are usually too proud and too lazy to do.

Eton finds itself in the throes of an identity crisis — caught between tradition and wokeness

The disadvantage that the Collegers have, mind, is that they’re usually hung-over. In the scholars’ house the Eve of St Andrews is a miniature festival of misrule: the Wall Game players in the upper years are given a slap-up “sock supper”, at which they drink freely before returning to their accommodations for a morale-raising session of terrorising the first-years. (The Master-in-College, by tradition, retreats to his private quarters and locks himself in for safety.)

These first years are made to stand on a table in the senior common room and forced to sing the several verses of the Founder’s Prayer (an address to King Henry VI) in Latin from memory while being pelted with cushions and other less savoury objects. Then there’s a hearty singalong for all of obscene football chants and Latin diss-tracks (“globulos defrangete” [”smash their balls”] was the enthusiastic refrain of the madrigal a music scholar composed in my generation.

It is a game, in other words, that keenly honours its past. At the sock supper every year a toast is raised “In Piam Memoriam J.K.S.” — honouring J K Stephen, a 19th-century poet who was Keeper of the College Wall in the 1870s and, by repute, held the entire Oppidan Wall at bay singlehandedly on one occasion when his teammates overslept. Among his other distinctions JKS, who died in a lunatic asylum in his 30s, has been touted as a candidate to have been Jack the Ripper.

Another former Keeper of the College Wall, not mentioned in connection with the Ripper murders, is the present Prime Minister. I fancy he may have brought some of the spirit of the game with him.

Want more exclusive societies and practices? Here’s the modern face of the Bullingdon Club…

Become a Gentleman’s Journal member. Find out more here.

Become a Gentleman’s Journal Member?

Like the Gentleman’s Journal? Why not join the Clubhouse, a special kind of private club where members receive offers and experiences from hand-picked, premium brands. You will also receive invites to exclusive events, the quarterly print magazine delivered directly to your door and your own membership card.